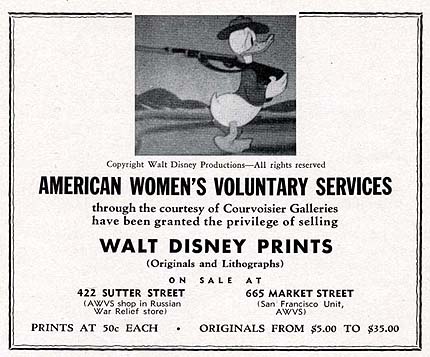

As this 1943 ad shows, if I had lived in San Francisco back then, and had been interested in animation, and had been well-heeled enough to have a few hundred dollars to spare, I could have probably put together a truly amazing collection of Disney cels. (One wonders which examples were impressive enough to rate a top-of-the-line $35 pricetag.)

Wonder if any of the ones that San Franciscans picked up back then are still proudly displayed anywhere in this city?