“Not many people know these are here.”

A cheerful employee of PoshPetCare is ushering me past two metal gates into her place of business’s forecourt. It’s March 2018, and I have been skulking around the dinky, house-like building on Hollywood’s Sunset Strip. The staffer has caught me standing on tippy-tippy-toe on the sidewalk outside, trying to take photos over a wall of imposingly tall shrubbery. Rather than telling me to scram, she’s being unexpectedly helpful.

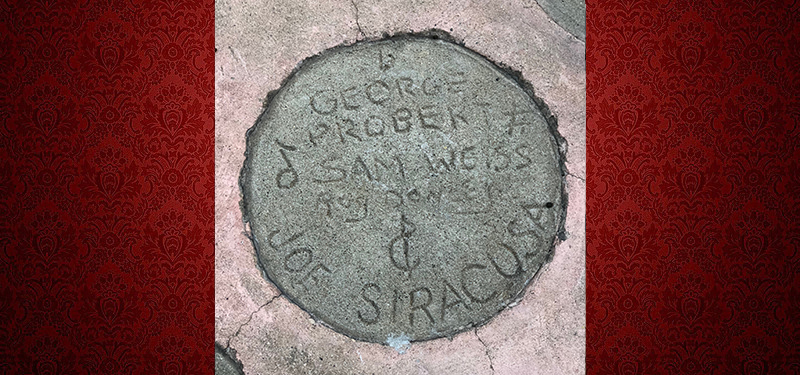

Once inside, I have the freedom to roam about shooting pictures of the pavement in front of the pet-grooming shop. More specifically, I’m able to document the 30 circular cement discs embedded there. Each is signed, usually with a date in the early 1960s and indentations where signatories had left prints of their elbows.

By now, you’re mystified—unless you’re a particularly serious Rocky and Bullwinkle fan. In that case, you may know that PoshPetCare’s home at 8218 Sunset Boulevard was once the headquarters of Jay Ward Productions, the cartoon studio that brought us the moose and squirrel’s adventures beginning in 1959. Back in the day, the dated signatures and elbow prints were accompanied by a statue of Bullwinkle hoisting Rocky on his left arm, which studio founder Jay Ward had commissioned in the fall of 1961 when The Bullwinkle Show came to prime-time TV. You didn’t need to be a Bullwinkle scholar to know about this statue, since it was readily visible from the street and stood for decades.

When I first started getting to Los Angeles in the late 1980s, it had been years since Jay Ward Productions had produced so much as a Cap’n Crunch commercial, let alone a TV series. But for a cartoon studio that no longer made cartoons, the company retained a surprisingly vivid presence on its longtime home, the Sunset Strip. And so I made numerous pilgrimages.

First, I’d visit Dudley Do-Right’s Emporium, a merchandise shop opened by Jay Ward in 1971. It was only open for a few hours a week, and everything seemed to cost either a quarter or more money than I could reasonably afford. Then I’d walk two doors down to pay my respects to the Bullwinkle statue, which—since it appeared to be made of papier mâché and often looked as if it wouldn’t survive the next serious downpour–I worried about as if it were a relative in failing health.

The Do-Right Emporium finally closed in 2005. In 2013, the Bullwinkle statue, in a state of dangerous disrepair, was removed for thorough restoration; after a lengthy absence, it returned last year and is now on a patch of public property on the Sunset Strip. Its refurbishment and relocation have received a fair amount of celebration, as they should.

But nobody has ever paid much attention to the elbow prints—which is understandable given that they tended to be overwhelmed by the moose who towered over them. I knew they were a parody of the handprints at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre. (You can leave an elbow print without putting down your martini, Ward reasoned.) I was aware that some of these prints were left there by The Bullwinkle Show’s supernaturally gifted voice-acting troupe: coproducer Bill Scott (Bullwinkle, Dudley Do-Right, and Mr. Peabody), June Foray (Rocky, Natasha, and Nell Fenwick), Paul Frees (Boris Badenov and Inspector Fenwick), Hans Conried (Snidely Whiplash), and William Conrad (the narrator). I sort of assumed the others belonged to additional studio personnel, a supposition often made by people who have mentioned the prints briefly when writing about the Bullwinkle statue.

But nobody has ever paid much attention to the elbow prints—which is understandable given that they tended to be overwhelmed by the moose who towered over them. I knew they were a parody of the handprints at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre. (You can leave an elbow print without putting down your martini, Ward reasoned.) I was aware that some of these prints were left there by The Bullwinkle Show’s supernaturally gifted voice-acting troupe: coproducer Bill Scott (Bullwinkle, Dudley Do-Right, and Mr. Peabody), June Foray (Rocky, Natasha, and Nell Fenwick), Paul Frees (Boris Badenov and Inspector Fenwick), Hans Conried (Snidely Whiplash), and William Conrad (the narrator). I sort of assumed the others belonged to additional studio personnel, a supposition often made by people who have mentioned the prints briefly when writing about the Bullwinkle statue.

When the friendly PoshPetCare employee gave me unfettered access to the forecourt, I realized that—Bullwinkle voice cast aside—most of the names on the cement discs were unfamiliar. It dawned on me that they might not all be Ward employees after all.

Back home, I started to dig up information on the elbow prints—and the Bullwinkle statue itself, since I realized I had only a vague understanding of its history. And then I tumbled down a rabbit hole of lore relating to the Ward studio, the businesses that surrounded it on the Sunset Strip, and 1960s Hollywood culture in general. It’s taken me more than three years to burrow my way back up to the surface—just in time for the 60th anniversary of the Bullwinkle statue, which was unveiled by Jayne Mansfield at an extravagant street party on September 20, 1961.

Here’s what I’ve learned. Fair warning: This will take a while.

Attack of the 15-Foot Woman

“Oh, God, to wake up in the morning with a hangover and look out and see that figure turning, turning, holding the sombrero—you knew what death would be like.”

—Gore Vidal, 1977 interview

You can’t discuss the Jay Ward Productions elbow prints without first discussing the Bullwinkle statue. And you can’t discuss the Bullwinkle statue except in the context of the giant showgirl figure who spun atop a silver dollar on the Sahara hotel’s towering neon sign in front of the Chateau Marmont hotel across the Sunset Strip. And even she requires some background explanation.

Let’s begin in October 1952, when the Sahara opened. The hotel/casino was the sixth such establishment to open on the Las Vegas Strip, which was starting to displace the Sunset Strip as the fulcrum of a certain type of celebrity-centric entertainment. (This transition was all but official: Billy Wilkerson, owner of the Sunset Strip’s swanky Trocadero and Ciro’s, went on to found the Flamingo in Vegas before being muscled out by Bugsy Siegel.) It made perfect sense that the Sahara would want to prospect for customers on Sunset.

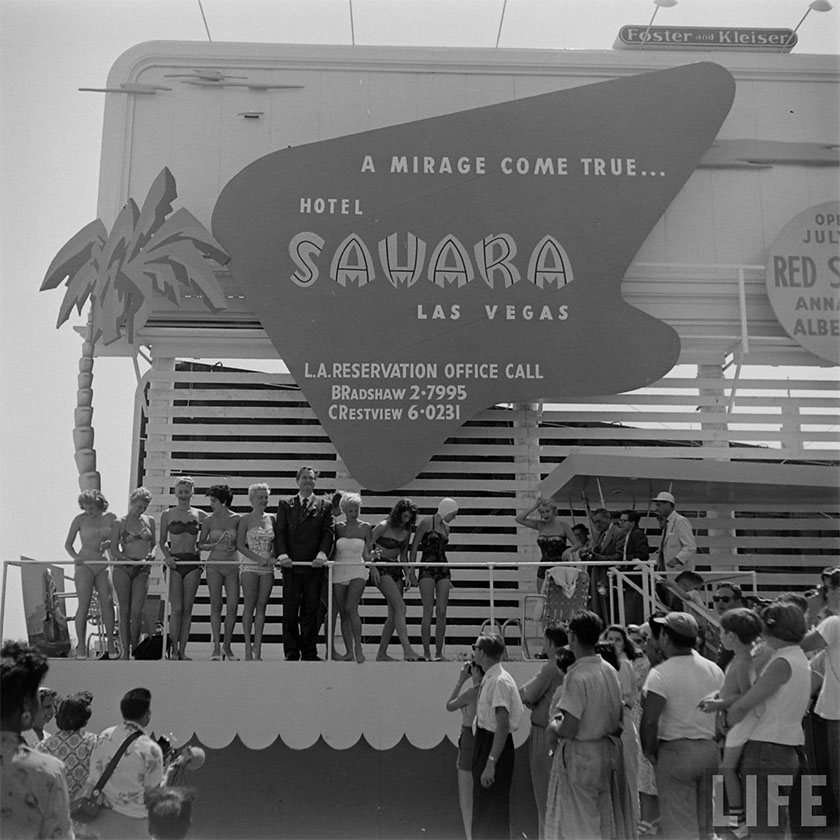

The hotel employed an intrepid entertainment director named Stan Irwin, who later produced The Tonight Show for Johnny Carson and voiced Lou Costello in Hanna-Barbara cartoons. When Irwin booked Red Skelton and Anna Maria Alberghetti to perform in the Sahara’s Congo Room, he promoted the engagement to Angelenos with a most unusual billboard at the corner of Sunset and Doheny. The sign incorporated a small swimming pool–filled with real water and real bathing beauties. A LIFE photographer captured the scene, complete with gawking bystanders.

According to one account, Irwin’s sign/pool was staffed by eight swimsuited women who worked in four-hour shifts. (Esther Williams supposedly waved every time she drove by.) The stunt was a publicity bonanza, but you can understand why it didn’t continue indefinitely. It’s also easy to see how the idea might have led to something similarly eye-grabbing but less labor-intensive. So instead of paying eight actual women, the Sahara erected a sign a mile and a half away with one giant sculpture of a woman wearing a swimsuit-like outfit and doffing a cowboy hat.

Life at the Marmont, a book about that august celebrity hideaway by Raymond Sarlot and Fred E. Basten, contains a passage about its guests being horrified when the Sahara’s “spectacular,” in signage industry parlance, went up in May 1957. It’s all very evocative. Except that the December 1956 issue of Signs of the Times, a signage-industry trade journal, includes a photograph of the showgirl and sign already in place. It’s the earliest contemporaneous reference I’ve found, although another later account says they dated to 1955.

Though the hotel-casino’s sign soon became associated with the Marmont, it actually sat on the same plot of land as a building that had once housed The Players—a nightclub/dinner theater/burger stand/barbershop owned by director Preston Sturges—before giving way to several short-lived eateries and ending up as the long-time home of the Imperial Gardens, a well-known Japanese restaurant. The sign was built by Electrical Products Corp., a major manufacturer of neon signage whose creations dotted the west coast. (The company was also responsible for a Sahara sign in San Francisco—with an animated neon version of the showgirl kicking her leg—that may have predated the LA one.) The sign on Sunset served a specific promotional purpose by announcing the performers appearing in the Sahara’s showroom and Casbah Lounge–who, in vintage photographs and film footage of the sign, include such notables as Martha Raye, Louis Prima and Keely Smith, Don Rickles, Jose Greco, Pat Boone, Liberace, and Kay Starr.

But it was the showgirl–all 15 feet and three inches of her, according to the earliest claim I’ve seen, though estimates varied considerably–that made the sign possibly a more Vegas-y artifact than anything that actually was in Vegas. A 1968 New York article by Lawrence Dietz, published soon after her removal, called her “the Sahara Lady,” and so will I henceforth. Accounts from the 1960s say that she was sculpted by a man named Rudy Vargas who worked for Silvestri Studio, a Los Angeles-based producer of mannequins, department-store window displays, and other figurative commercial art; his other works included a giant minuteman for a Canoga Park bank and a pony express rider and his steed commissioned by gambling tycoon Bill Harrah. He was apparently the same Mexico-born Rudolph Vargas who created figures for Disneyland attractions such as It’s a Small World and Pirates of the Caribbean, and whose real passion was producing religious wood carvings, including a Virgin Mary that ended up in the Vatican Collection.

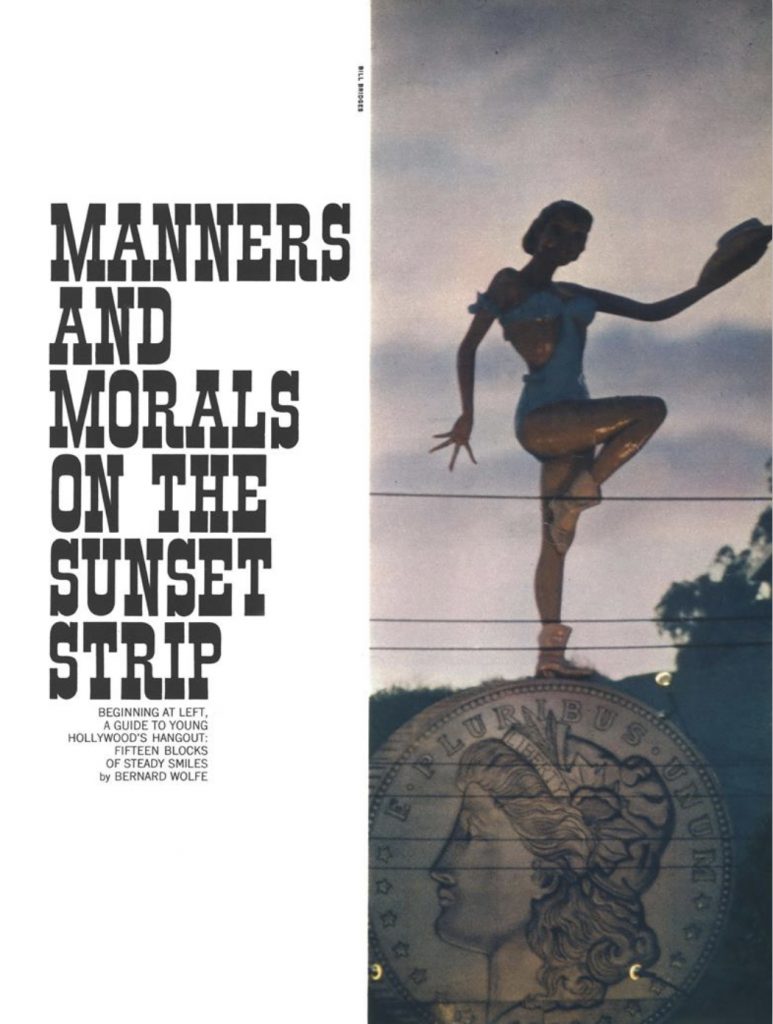

This photo from that 1956 Signs of the Times article shows Vargas’s Sahara figure in her showgirl suit (with peek-a-boo bodice) and boots, balanced on one foot and waving her cowboy hat. For the moment, you’ll have to imagine her spinning for yourself, but stay tuned.

Here’s a color photo–which, judging from the Sahara performers being touted, was taken at around the same time–with a bit more context of the neighborhood circa 1956. That’s the Imperial Gardens—more recently the well-known nightclub the Roxbury—behind the sign.

Here, courtesy of Dave DeCaro of the excellent Daveland site, is a 1957 photo showing the Chateau Marmont and the back of the Sahara sign—although the Sahara Lady’s 360-degree gyrations allowed her to be viewed in full from the hotel as well as the street. Directly across the Strip on the right, you can see a small white building with a peaked brown roof. Built in 1923 and originally a house, it spent the late 1950s serving as the address of such businesses as a modeling agency, an acting school, and a small music publishing company cofounded by Davy Crockett actor Fess Parker, who reportedly owned the place. A few years after this photo was taken, it would become the home of Jay Ward Productions, placing the studio almost literally in the Sahara Lady’s shadow.

The Sahara sign stayed up for over a decade, which was an unusually long run for something that was ultimately a glorified billboard. We can assume that the hotel/casino found it an uncommonly effective form of advertising. However, Life at the Marmont reports that Chateau Marmont guests were appalled–especially those whose rooms overlooked the sign–and petitioned for its removal. The book also says that the Marmont’s owner remained surprisingly unfazed and may have been receiving payments relating to the sign’s obstruction of views from the hotel.

People tended to see the Sahara Lady as an emblem of the Sunset Strip, for better or (more often) worse. Theater columnist Brooks Atkinson wrote a column calling her an “outsize floozie” and “tanned trollop,” and though he claimed that nobody out and about on the Strip paid attention to her, he certainly did. So did everyone else who wrote about the Sunset Strip. When I came across a cover-featured article on the Strip in the August 1961 Esquire, I didn’t have to turn to the story to know it would show the Sahara Lady (as its opening art) and reference her in the text (“a brightly painted, fifteen-foot-tall representation of a shapely chorus girl in skimpy tights and striking a drum-majorette pose, one enticing leg raised as if to take a step”). Esquire’s piece saw her as a metaphor for the Strip’s human denizens, “forever on the brink of some meaningful act, ready to step out smartly, but not knowing which direction to take or what destination to head for, turning as on a spit under the constant brazier of a sun, propped up by nothing but dollars, face frozen in a stage-front smile, endowed with human form, but as purposeless as shish kebab.” (Stephen Manes alerted me to the fact that the article’s author, Bernard Wolfe, was also a former bodyguard/secretary to Leon Trotsky, friend of Anais Nin and Henry Miller, science fiction author, and pornographer.)

As recounted in Shawn Levy’s 2019 book The Castle on Sunset: Life, Death, Love, Art, and Scandal at Hollywood’s Chateau Marmont, Ring Lardner Jr., John Cheever, and Gore Vidal all resided at the Marmont at various times while screenwriting in Hollywood and worked with the Sahara Lady rotating outside their window as an uninvited muse. (Cheever even wrote her into a 1961 New Yorker story.) According to Levy, actor Paul Muni, another Marmont guest, hated her with an obsessive fury: “‘It’s the whore Hollywood! The whore show business!’ he bellowed into the night.” Child star Brandon deWilde supposedly shot at her with an air rifle.

Maybe the Sahara agreed with Brooks Atkinson that the Sahara Lady was so overwhelmingly familiar a presence that she ran the risk of being ignored by passers-by. The hotel removed the massive silver dollar she stood upon at some point, whereupon she began spinning right above the neon SAHARA. In the mid-1960s, her blue outfit gave way to gaudier red, white, and blue pinstripes, and different photos show her in both boots and heels.

Her hairstyle and facial features also changed noticeably: She initially looked like a pretty tough dame, and later bore a resemblance to—I don’t think I’m imagining this—Jacqueline Onassis. A 1966 photo shows Liberace promoting an engagement at the Sahara by lighting a giant candelabra in the Sahara Lady’s hand; she sports an impressive bouffant hairstyle which (it just dawned on me) must have been temporary and an allusion to Liberace’s own bushy ‘do.

And in this clip from Mondo Teeno (1967), she seems to be wearing a hat rather than waving one.

But the most significant thing that happened to the Sahara Lady over the years didn’t involve her outfit, hairstyle, or perch above the Strip. It was the fact that she got company across the street, in the form of a swimsuit-clad moose and his flying-squirrel compatriot.

Operation Loudmouth

“On a little patch of land just outside the city limits of Los Angeles, on that portion of Sunset Boulevard which is called Sunset Strip, there is a large billboard that advertises a casino in Las Vegas. Set on top of the billboard, dressed in red boots, long red gloves, and black-and-white striped panties attached across the midriff to a red bikini top, is an immense, pink plaster chorus girl. One of her arms is bent, hand slightly forward and upraised, at the elbow. Her other arm extends, fingers outstretched, behind. One of her knees is raised. The other leg is the one she stands and slowly, continuously rotates on. Diagonally southwest across the street from the girl, much nearer the ground, on a little pedestal, another figure in red gloves, striped panties, and red top rotates, in a similar pose. It is Bullwinkle the Moose.”

—Renata Adler, “Fly Trans-Love Airways,” The New Yorker, February 25, 1967

When Rocky and His Friends debuted in an afternoon slot on ABC starting in the fall of 1959, the press took the cartoon—the first program featuring Rocky and Bullwinkle—to be a kids’ show and didn’t pay much attention. A year later, Hanna-Barbera’s The Flintstones made prime-time cartoons hip, prompting NBC to buy The Bullwinkle Show and schedule it on Sunday nights at 7:00 p.m. starting on September 24, 1961. Suddenly, the moose and squirrel’s adventures were fodder for TV reporters and critics. Which meant that like any other major TV program, they were worthy of a public-relations campaign.

Except this was no standard PR blitz: It was engineered by Jay Ward, whose approach to business was as idiosyncratic as the cartoons his company produced. Devised in collaboration with publicist Howard Brandy–a Bullwinkle fan who’d worked with Frankie Avalon and Fabian–the project was known as “Operation Loudmouth.” Ward’s goal, according to a syndicated column by Ken Murphy, was “to convince people that his shows, such as The Bullwinkle Show, are essentially adult.” Murphy quoted Ward on TV cartoons: “Our show, and others too, are meant for an adult audience; they’re usually sophisticated satirizations on well-known subjects or people.”

In the weeks leading up to Bullwinkle’s prime-time debut, Jay Ward and coproducer/head writer/Bullwinkle voice Bill Scott hosted two parties. One, on August 24, 1961, was a classic Hollywood premiere at the Screen Directors’ Guild Theater, with a red carpet and Klieg lights; the 450 attendees included TV stars James Garner and Will Hutchins. Ward and Scott presided in white tie, tails, shorts, and sneakers.

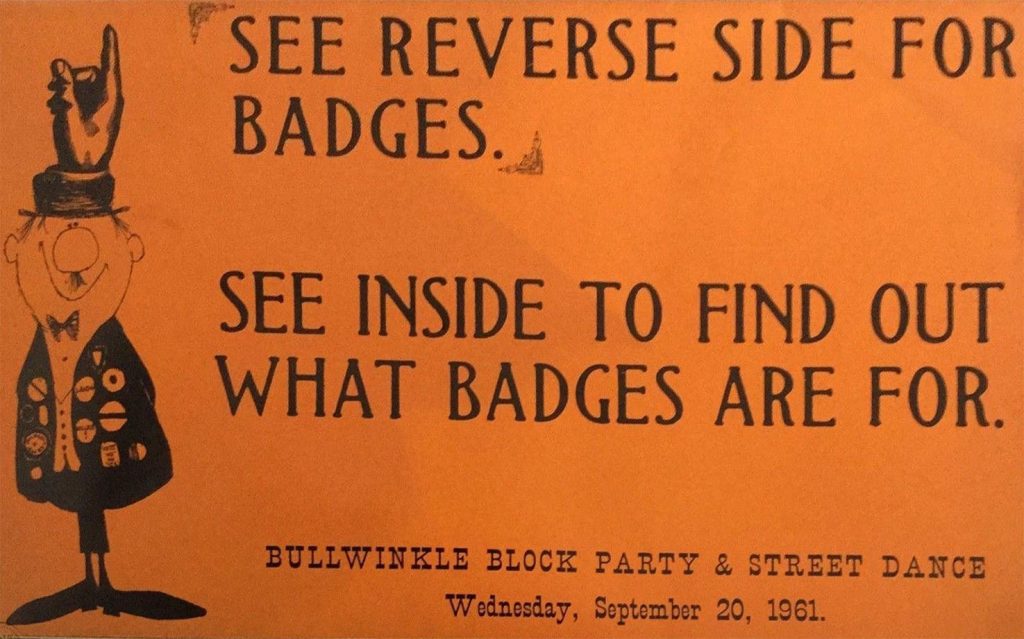

The other bash, on Wednesday, September 20–Jay Ward’s 41st birthday–was held in the area surrounding Jay Ward Productions headquarters at 8218 Sunset. That gala was called Bullwinkle’s Block Party and Street Dance and featured the unveiling of the Bullwinkle statue.

As Keith Scott’s The Moose That Roared details, PR man Brandy took credit for the idea of erecting a statue of Bullwinkle in front of the studio: “I had become a statue nut while I was living in London,” he explained. Once that notion came up, having the moose strike the same pose as the Sahara Lady—who dominated the view from the studio’s front windows-would have been the most logical decision in the world, at least if you worked for Jay Ward. The studio’s cartoons frequently riffed on show-business culture: In Jet Fuel Formula, the first Rocky and Bullwinkle storyline, moon men Gidney and Cloyd had ended up as Vegas entertainers, performing at “The Deserted Inn.”

Other cartoon studios acknowledged Las Vegas, too—Bob Clampett’s Beany and Cecil vacationed in “Lost Wages” in 1962’s So White and the Seven Whatnots—but lacking Ward’s zeal for zany promotional stunts, they would have been less likely to channel their satiric impulse into sculpture, even if the Sahara Lady had been staring them in the face from across the street.

The Bullwinkle statue was built—at a reported cost of $6,000–by Bill Oberlin, a former employee of Warner Bros.’ cartoon studio and set decorator for Clampett’s Time for Beany puppet show. (He was also a part-time professional W.C. Fields impersonator.) A 1961 Variety article described Oberlin as an assistant producer of The Bullwinkle Show, though his own description of his work for Ward involved doing clay modeling—“I got tired of doing flat work,” he said in a 1971 Los Angeles Times story on his Fields mimicry—and The Moose That Roared mentions him doing general odd jobs at the studio.

While the Sahara Lady brandished a hat in one hand, Bullwinkle held Rocky, in a pose familiar from the cartoons. The Sahara Lady wore a glamorous, revealing outfit; the moose wore an old-fashioned red-and-white striped swimsuit of the sort that resembled long underwear. Both statues rotated, with his motion supposedly synchronized to match hers. She stood atop a giant silver dollar; his base was decorated with moosehead coins that photographs indicate were gone within a few years. (They must have been tempting targets for theft.)

(Side note: A couple of months after Bullwinkle’s Block Party, a far larger three-dimensional depiction of the moose in a red-and-white bathing suit joined the balloons in Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, a feat which Jay Ward and Howard Brandy must have considered a coup. This 64-foot moose—manufactured from 500 square feet of neoprene-covered nylon by Goodyear—became a staple of the parade until 1983, familiar to millions of Americans who never knew about his shrunken fraternal twin on the Sunset Strip.)

As with the Sahara Lady, every article about the Bullwinkle statue seems to quote a different height: 14, 16, 18, 20, or 30 feet tall. In 2017, when the City of West Hollywood sought bids for construction of a new base for Bullwinkle and Rocky to stand on, it stated that the statue was 16 feet tall and weighed 700 pounds. If that’s correct and the Sahara Lady was indeed 15 feet 3 inches, as stated in the 1956 Signs of the Times story, she was slightly less statuesque than the moose, and towered over him only because she was perched on a Vegas-class piece of signage.

The Sahara Lady may have been manufactured using a particularly durable, plaster-like material called Hydrocal. Bullwinkle was nowhere near as resilient. For years, I thought that he was made out of papier mâché, but the West Hollywood bid document provides a detailed list of the original construction materials: “wood, steel plates, solid steel rods and tubes, chicken wire, bailing wire, rebar, pipe fittings, plumbers strapping tape, newspapers, non-compression foam, cardboard, fiberglass, plaster and plaster bandages and exterior house paints.” The papier mâché was slathered on later, a decision which helps explain why Bullwinkle and Rocky often looked so beat up, at least from the 1980s onward.

A “Bullwinkle’s Fan Club” segment referenced famed starlet Jayne Mansfield as one of the big names appearing on a telethon operated by Rocky and Bullwinkle—just her name, on a card. For Bullwinkle’s Block Party, Ward secured the presence of the real deal. Richard Soper’s book Affectionately, Jayne Mansfield called 1961 “a disappointing year for Jayne’s career,” which helps explain why she was available to unveil the Bullwinkle statue; a day later, she flew to Tuscon with bodybuilder husband Mickey Hargitay and presided over the opening of a discount store called Thrift City. (Some of Mansfield’s publicity efforts involved unveiling herself: Five days before the Block Party, a newspaper article reported that she had recently crossed Rossmore Ave. in Hollywood in a bikini—while filming The George Raft Story—and had been told by police to put on a robe next time.)

Even the prospect of the Block Party helped Ward and Brandy generate publicity for The Bullwinkle Show. Los Angeles Herald & Express motion picture editor Jimmy Starr mentioned it in two columns in the days leading up to the event. “Jay Ward and Bill Scott (they dream up ‘The Bullwinkle Show’) are going to have a ‘block party’ right on Sunset Boulevard Sept. 20–an 18-piece ork, stars, pushcarts, organ grinders (mit monkeys) and other gimmicks just for the unveiling of a statue of Bullwinkle (a moose),” he wrote. “What will Hollywood think of next? … bet the police dept. just love Ward and Scott.”

One notable member of the police force—Los Angeles County Sheriff Peter J. Pitchess—did love Jay and Bill. Or at least he accepted their invitation to be a guest of honor at the Block Party. (“He was hesitant about it until we got Jayne Mansfield as a guest of honor too,” said Bill Scott in a 1982 interview in a punk fanzine called Stop.) The Ward studio sat in what was an unincorporated section of the county at the time—it’s now the City of West Hollywood—and if you were planning to hold a large and raucous outdoor event, it couldn’t have hurt to butter up your neighborhood’s top lawman.

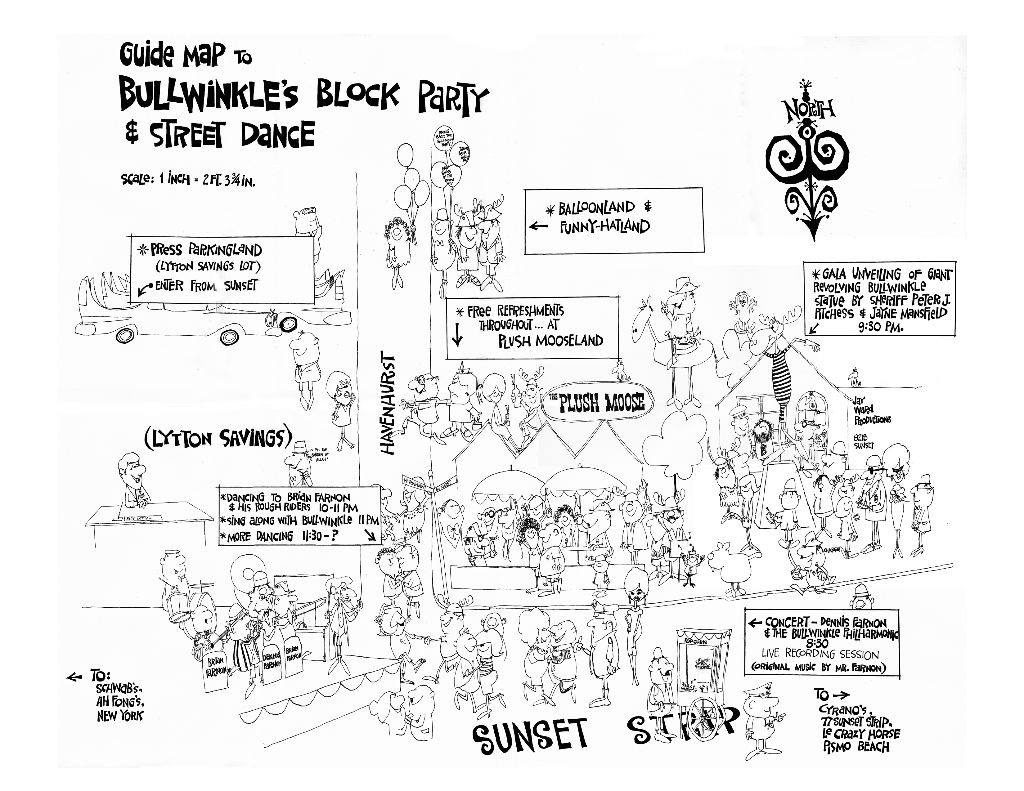

With Pitchess on its side, Bullwinkle’s Block Party took over the neighborhood, or at least the portion of it surrounding Jay Ward Productions’ side of Sunset. Catering services were provided by the Plush Pup, an adjacent hot-dog stand which became the Plush Moose for the evening. (Its building later housed Dudley Do-Right’s Emporium.) Parts of both Sunset and Havenhurst, a side street, were roped off for dancing and dining. If a November 1961 column by the Los Angeles Herald & Express’s Bill “Mr. L.A.” Kennedy is to be believed, even the Liberty head on Sahara Lady’s giant silver dollar was pasted over with a drawing of Bullwinkle—tantalizing evidence that the Sahara and/or those responsible for its sign took Ward’s lampoonery good-naturedly, at least at first.

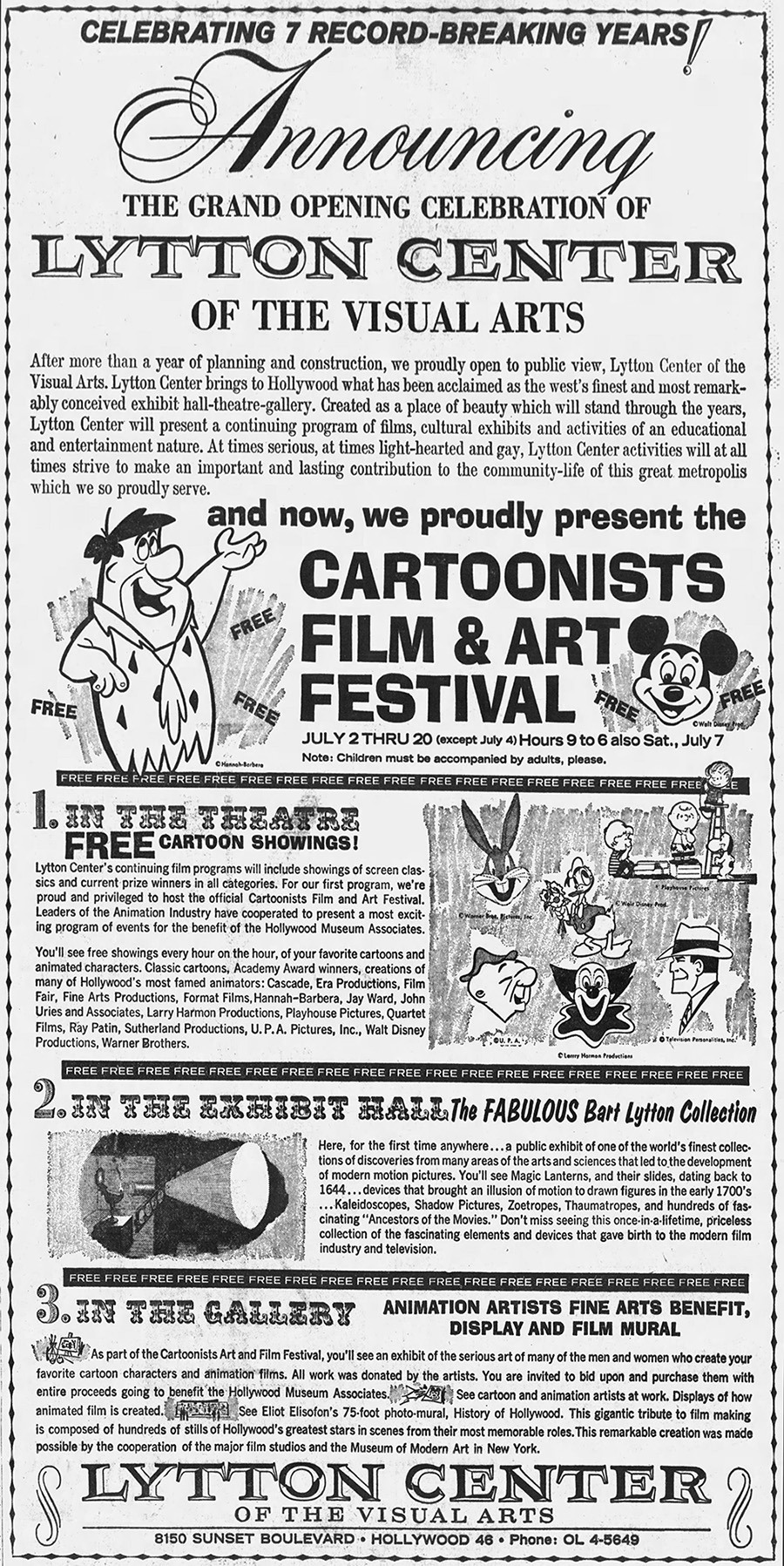

Across Havenhurst, the parking lot at Lytton Savings was reserved for members of the press attending Ward’s gala. The bank was founded by Bart Lytton, a former journalist, publicist, and communist who would open the Lytton Center for the Visual Arts, a movie museum, in a separate building on the same plot of land as his bank in July 1962. Its grand opening featured a cartoon festival with films and art from Lytton’s neighbors at Jay Ward Productions, as well as numerous other major and minor Hollywood animation studios. The following ad is worth sharing even though it has nothing to do with the Bullwinkle statue.

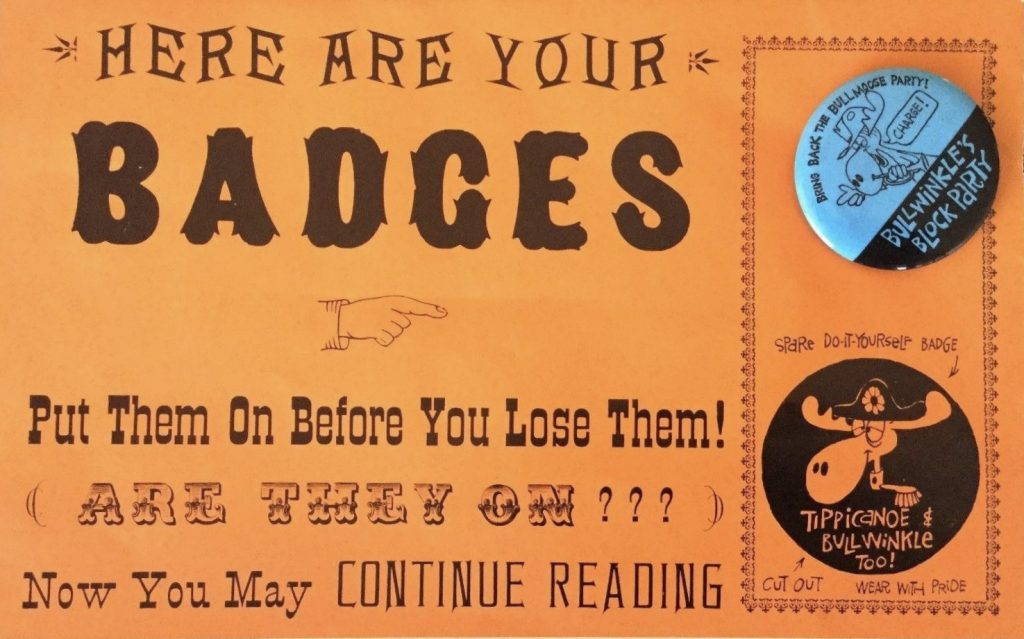

Bullwinkle’s Block Party attendees received some goodies, and fortunately for those of us who couldn’t attend, examples have survived.

Courtesy of Lisa Kurtz Sutton of Facebook’s Moosylvania Farkling Squad group, here’s the fold-out map of the evening’s festivities, which was drawn by Ward staffer (and future Mary Tyler Moore Show cocreator) Allan Burns and featured “lands” such as Balloonland, Funny-Hatland, Plush Mooseland, and (in the Lytton Bank lot) Press Parkingland. Live music was provided by two groups led by brothers: Brian Farnon and His Rough Riders and Dennis Farnon and the Bullwinkle Philharmonic.

Jay Ward Productions announced that it had invited Marlon Brando, Tony Curtis, Bobby Darin, Rock Hudson, Kim Novak, Jack Paar, Frank Sinatra, and Elizabeth Taylor to Bullwinkle’s Block Party—not that any of them actually came. At least one celebrity—Bob Denver, at the time best known for playing Maynard G. Krebs on Dobie Gillis, and later the guest on a 1963 episode of Ward’s Fractured Flickers—did turn up. According to Kristine Dunn of the Miami News, others among the 4,000 attendees included “actors, actresses, publicists, newsmen, photographers, call girls, and freeloaders.” Ward claimed the throng consumed 10,000 soft drinks, hundreds of gallons of coffee, and 3,000 bags of popcorn.

I am infinitely grateful to Keith Scott for sharing some rare audio of Bullwinkle’s Block Party from his collection. In this clip, Bill Scott welcomes attendees and introduces Dennis Farnon’s Bullwinkle Philharmonic, which played “a program of themes from The Bullwinkle Show.” (Other music that night included dance tunes such as “Why Don’t You Do Right,” which had nothing to do with a certain Mountie.)

Despite the zeal with which he promoted The Bullwinkle Show, Jay Ward was a profoundly shy man; when Bullwinkle fans spotted him at Dudley Do-Right’s Emporium, he was known to deny that he was, in fact, Jay Ward. But here he is speaking at the Block Party, followed by a performance of “The Moosylvania March.” This clip combines the audio Keith provided with a different chunk from The Jay Ward Music Cassette, a tape sold at Dudley Do-Right’s Emporium.

The recording of Ward’s comments is muffled—as best I can tell, here’s what he said about the statue and its surroundings on the Sunset Strip, which then segues into a parody of Emma Lazarus’s Statue of Liberty poem, “The New Colossus.”

In this statue which we are about to unveil, we feel that people can look for world life at its best. As the Colossus of Rhodes, the Tower of Babylon, the Great Pyramids, the Eiffel Tower all once summed up the best in life of previous times.

Perhaps it is particularly important that such a symbol be located in an area renowned for its mature influence on our community. The stability of its citizens. The sound common-sense virtues and amplified folksiness of its atmosphere, and the high regard for culture and beauty.

We must all experience the thrill of truth and honor as we see this new beacon, symbolic of 20th-century man, thrusting upwards to the heavens. This symbol of hope for the entire free world. Were it to speak it would say boldly, “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled mooses yearning pay TV. The wretched refuse from your nightly chores. Send me these, the showless, the storm-tossed NBC. I lift Rocky by Jay Ward Productions’ doors.”

What Jayne Mansfield and Sheriff Pitchess had to say during the ceremony remains a mystery.

Sadly, there also isn’t a profusion of readily-available photographic documentation of Bullwinkle’s Block Party. (One 1961 article says that Ward was going to videotape the festivities for broadcast on The Bullwinkle Show; it would be a miracle if that survived and resurfaced.) Louis Chunovic’s The Rocky and Bullwinkle Book does include this fine photo of Scott (dressed as Teddy Roosevelt–the event had an official “Bring Back the Bullmoose Party” theme), Mansfield, Pitchess, and Ward (in a Cleveland Indians uniform). They’re standing in front of art by Allan Burns.

Here, from a 1961 newspaper report, are Scott, Ward, Pitchess, and Mansfield, apparently moments before the unveiling, which was scheduled for 9:30 p.m. (and which one article said proved unexpectedly difficult to perform until someone helped Mansfield whisk off the cloth).

![]()

Here’s a UPI photo from the Los Angeles Mirror showing Scott, Mansfield, Bullwinkle, Rocky, and part of the crowd.

And here are a triumphant Scott, Pitchess, and Ward with the freshly-unveiled statue.

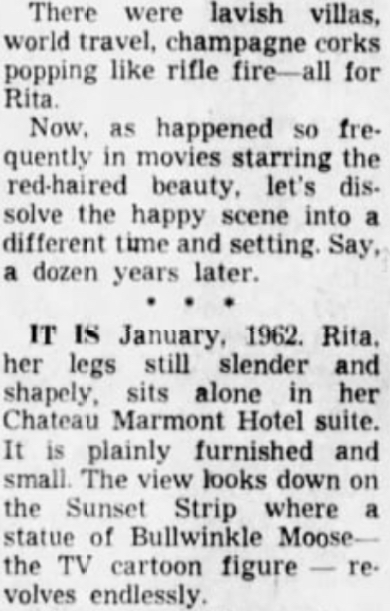

Bullwinkle soon established himself as part of the Sunset Strip scenery. Four months after he arrived, Hollywood reporter Vernon Scott’s story on the sad state of Rita Hayworth’s career took the fact that her Chateau Marmont room overlooked the rotating moose as a sign of how far she’d fallen (whether Miss Hayworth would have preferred a view of the Sahara Lady, I’m not sure).

Here’s the statue as you would have seen it if you’d strolled by Jay Ward Productions in the years immediately after Bullwinkle’s Block Party.

This photo is one of the rare ones showing moose, squirrel, and showgirl all in one shot.

Note that in both of the photos accompanying this article that depict both Bullwinkle and the Sahara Lady, each figure is facing the same direction—bolstering the theory that his 360-degree turns were originally synchronized with hers. The Ward studio also repainted the moose’s bathing suit at least once in the 1960s to bring it in line with the showgirl’s updated costume—but let it be known that Bullwinkle appears to have been the first of the two to wear gloves.

Bullwinkle, Rocky, and Jay Ward Productions also appear in artist Ed Ruscha’s famous 1966 fold-out book Every Building on the Sunset Strip, which—four decades before Google Street View—documented the Strip as it looked in 1966. His photo shows the moose wearing a repainted bathing suit with vertical stripes and cutouts, emulating the Sahara Lady’s new outfit (the Sahara Lady herself was too high up to be captured by Ruscha’s camera).

Ruscha has made numerous return visits, and the Getty Research Institute’s amazing 12 Sunsets site lets you virtually cruise the Strip and see the Bullwinkle statue, 8218 Sunset, and their neighbors as they appeared in 1966, 1973, 1974, 1975, 1985, 1990, 1995, 1997, 1998, and 2007. (This sequence of images suggests that the statue may have stopped rotating sometime in the 1970s.)

Speaking of 1960s artists, Deborah Davis’s book The Trip: Andy Warhol’s Plastic Fantastic Cross-Country Adventure, which recounts Warhol’s 1963 trip to Hollywood, has a memorable moment involving him tooling down Sunset Boulevard in a Ford Falcon and taking in Bullwinkle and the Sahara Lady. The book doesn’t specify what Andy thought of them—other than saying that he was dazzled by the Strip’s signage in general—but it’s fun to toy with what the legendary pop-culture aficionado might have made of the two figures.

The Sahara Lady’s status as an unofficial symbol of the Sunset Strip in the 1960s is reflected in the fact that she smiled and twirled in two 1964 movies: William Castle’s The Night Walker (narrated by Jay Ward Productions’ own Paul Frees) and Franklin J. Schaffner’s The Stripper. The latter movie–starring Joanne Woodward as the title character–is particularly pertinent to this article, since it opens with a shot of the showgirl and her sign and then pans over to introduce Woodward, with the Ward studio and Bullwinkle statue visible in the background. (There’s also a bonus Jayne Mansfield reference.)

Mondo Hollywood (1967), a controversial documentary that crams in everyone from Ronald Reagan to Brigitte Bardot and often feels like a bad trip, features four tantalizing seconds of Bullwinkle and the Sahara Lady spinning in one shot, although not synchronized with each other.

The Bullwinkle statue also pops up, Zelig-like, in mid-1960s footage involving Jay Ward Productions’ neighbors on the south side of Sunset. Here it is spinning away at the start of a clip from Mondo Mod, a 1967 documentary featuring Belinda, a fashionable boutique next door to Jay Ward Productions which was said to have introduced the miniskirt to Los Angeles.

Today, Belinda proprietor Charles Lange says that he “got to know Jay and his merry band of art directors and illustrators well” from 1966-1969 and became lifelong friends with Ward animator Don Jurwich.

Young People Speaking Their Mind

There’s something happening here

But what it is ain’t exactly clear

There’s a man with a gun over there

Telling me I got to beware

—“For What It’s Worth (Stop, Hey What’s That Sound),” Buffalo Springfield

One of the best ways to get a sense of the quirky milieu that surrounded the Bullwinkle statue is to watch this 1967 stock footage showing the statue and Jay Ward Productions in context with their eclectic neighbors on the south side of Sunset Boulevard.

The above clip includes:

-

- The Body Shop, a strip club, still extant in 2021 and no relation to the skincare chain;

- The Fifth Estate, a coffee shop/hangout with a literal underground newspaper, the Los Angeles Free Press, headquartered in its basement;

- Belinda;

- Jay Ward Productions and the Bullwinkle statue;

- The Plush Pup, which catered Bullwinkle’s Block Party and later gave way to Jay Ward’s Do-Right Emporium;

- Behind the Plush Pup, another Jay Ward Productions building, which Keith Scott notes was where Jay Ward himself spent most of his time tending to business affairs;

- Lytton Savings, which loaned its parking lot to the Ward studio for Bullwinkle’s Block Party and had the same googie-style zig-zag roof as the Plush Pup, leading to them looking like the same building in two sizes;

- Sunset Steak N’ Stein, a steak house in the building that formerly housed Googie’s, the coffee shop that gave googie architecture its name;

- At the very end, and not very recognizable, iconic Hollywood hangout Schwab’s Pharmacy.

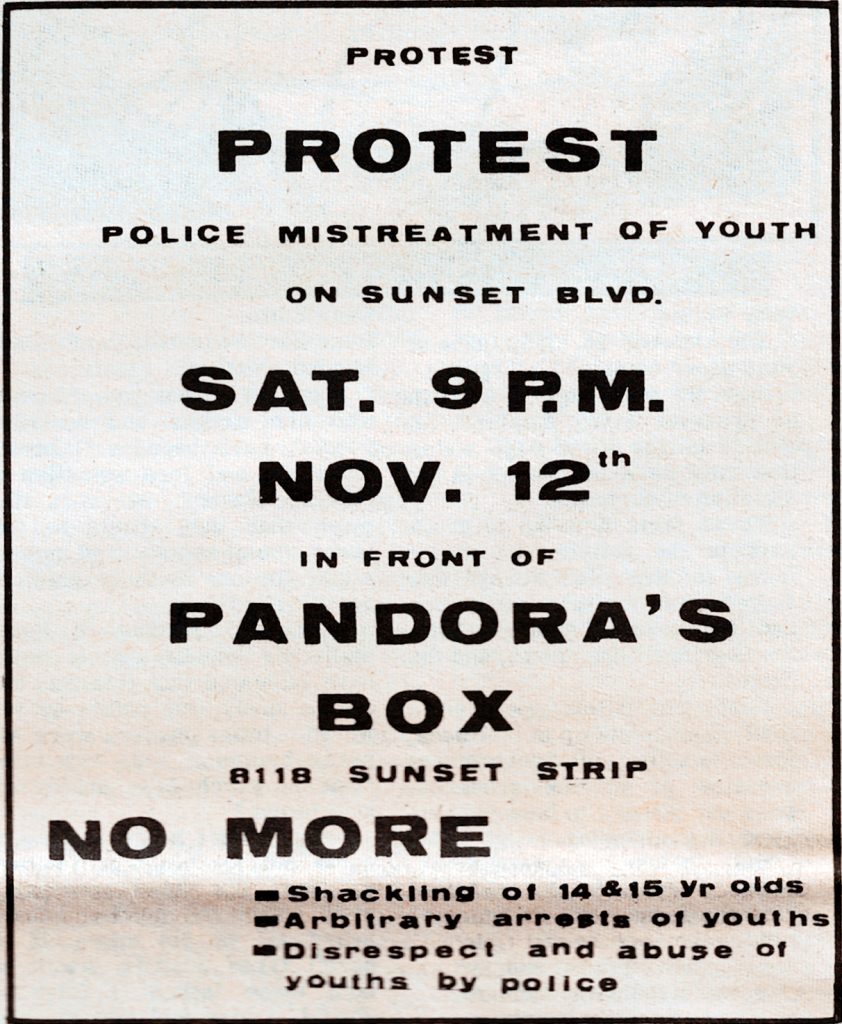

Oh, and a little bit before we get to Schwab’s and Steak N’ Stein, you will see Pandora’s Box, a nightclub—out of business when this footage was shot, but still attracting loiterers—that was a three-minute walk from the Ward studio. It was located across from Lytton Savings on a traffic triangle at the particularly busy intersection of Sunset and Crescent Heights. Originally a jazz club, it became a teen hangout with no alcohol license and an all-ages policy. The Beach Boys, The Byrds, The Doors, and Sonny and Cher all performed there.

Pandora’s Box was one of several clubs on the Strip that catered to underage kids and gained reputations for sex and drugs as well as rock and roll, not to mention drinking and general unruliness. Grownups—some of whom pined for the era when the strip was synonymous with Ciro’s and other landmarks of Hollywood swank—were not thrilled by their impact on the area. In a twist that sounds like a bizarre conflation of Chinatown and Footloose, a member of the Los Angeles Board of Supervisors named Ernest E. Debs envisioned tearing down the teen nightclubs and replacing them with office buildings, as well as building a highway to connect this new business district with the rest of LA.

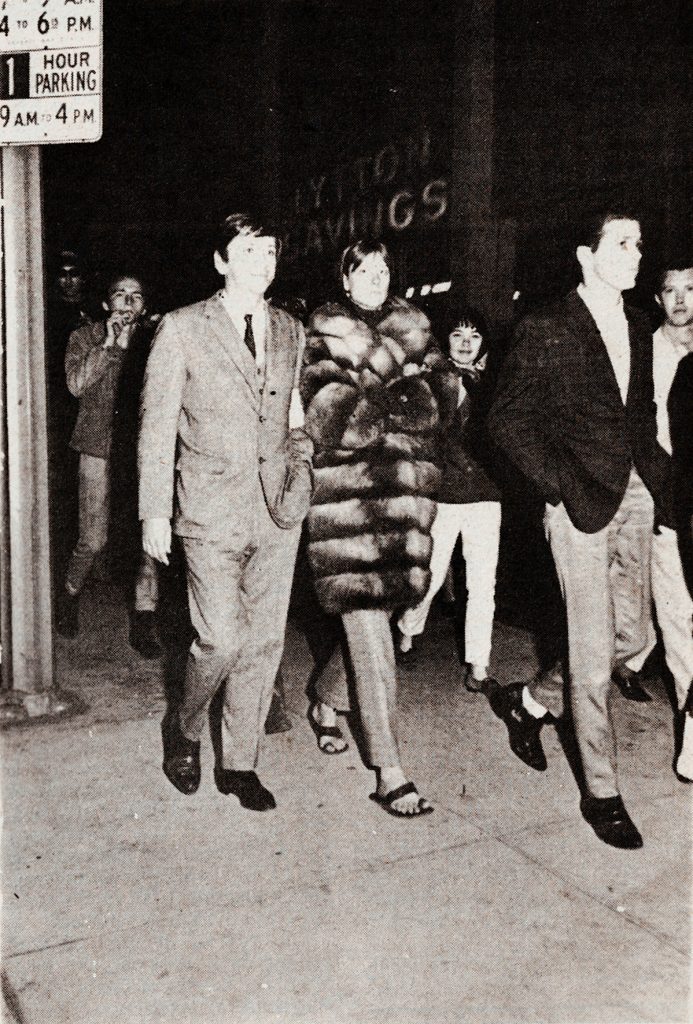

The poor reputation of Pandora’s Box and other nearby clubs led to the enforcement of a law mandating a curfew for those under 18. That resulted in protests and face-offs between young people and police officers, culminating on the night of November 12, 1966. Outside Pandora’s Box, the crowd included Jack Nicholson, Peter Fonda, Sonny and Cher, and Bullwinkle’s Block Party attendee Bob Denver. Throngs of sign-waving protesters disrupted traffic on the Strip. And in what sounds like the scariest moment, protesters overwhelmed two buses.

A full examination of the drama that roiled the Strip is beyond the scope of this article; Riot on Sunset Strip, an excellent book by Domenic Priore, tells the story in whole. But Jay Ward Productions’ office at 8218 Sunset stood almost precisely halfway between Pandora’s Box and the Fifth Estate coffee shop, the latter being another key gathering spot for young people opposed to the curfew. So as protesters went marching up the Strip, they stomped right past the Bullwinkle statue, as shown in this clip from a documentary called The Forbidden (1966).

Here’s a color clip, apparently also from the November 1966 protests, panning from Bullwinkle to the Sahara sign (with a blip in the middle).

Mondo Teeno included a brief shot of Bullwinkle and Rocky amid shots of rowdy crowds on the strip and musings about the enigma of teenagers.

We can be grateful that all of these pieces of footage pause to show Bullwinkle and Rocky spinning; you can imagine why the camera operators in question got distracted. (Meanwhile, Belinda proprietor Charles Lange reports that he placated the crowd outside his shop by projecting the original 1933 King Kong on its window.)

The cultural legacy of the Pandora’s Box protests and riot include the fact that they moved Stephen Stills to write “For What It’s Worth (Stop, Hey What’s That Sound),” a song performed by his group Buffalo Springfield. (It had been the house band at the Whisky a Go Go, a couple of miles up Sunset from Pandora’s Box.) The tune is often mistakenly believed to be an anti-Vietnam War anthem, and I didn’t realize its actual inspiration myself until I began researching this article, perhaps because it doesn’t mention Bullwinkle. Neither did a lesser-known song said to be about the protests, the Monkees’ “Daily Nightly”—but its writer, Mike Nesmith, surely referenced the showgirl in the line “Sahara signs look down upon a world that glitters glibly.”

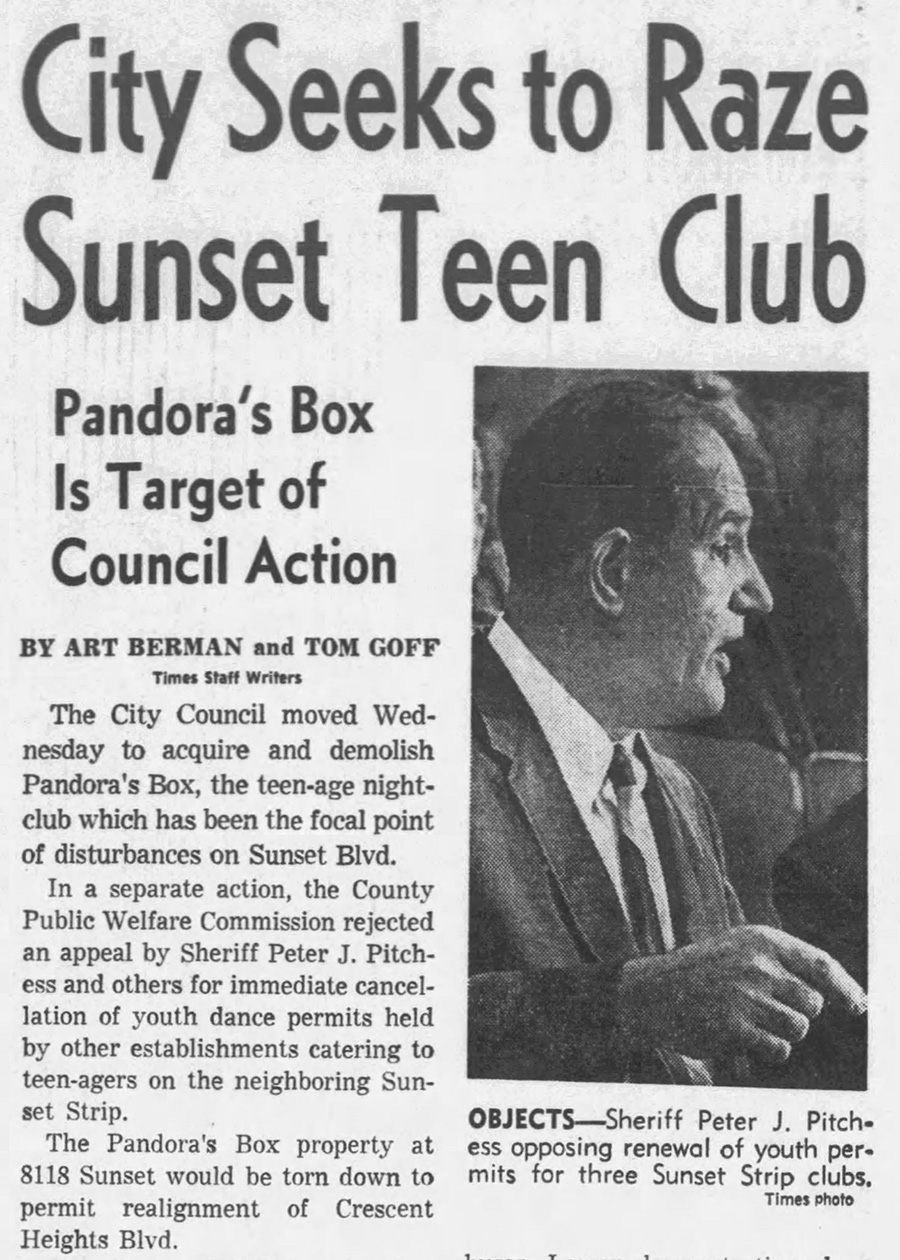

Days after the protests and riot, local officials exacted their revenge on Pandora’s Box by moving to acquire and demolish the club, which was indeed knocked down in August 1967. Here’s the Los Angeles Times’ headline on the matter, accompanied by a photo of Sheriff Peter J. Pitchess, who probably pined for the days when his biggest problem was revelers dancing in the street at Bullwinkle’s Block Party.

Pandora’s Box wasn’t the only institution in Jay Ward Productions’ neighborhood to be demolished in this time frame. The Sahara Lady also vanished from the scene, freeing up space eventually occupied by a Marlboro Man billboard that became widely associated with the Strip in its own right.

As with the exact date when the showgirl and her sign went up, it’s tough to pinpoint when they came down. Life at the Marmont and most other 21st-century sources that specify a year say that it happened in 1966. However, the sign is still visible in film footage of the Pandora’s Box drama transpiring in mid-November of that year. And Renata Adler’s February 1967 New Yorker article on the Strip opens with a present-tense reference to the Sahara Lady and Bullwinkle twirling across the street from each other.

Mentions of the Sahara sign’s disappearance published in the late 1960s are vague and inconsistent. An October 1968 Baltimore Sun article says it was removed “about eighteen months ago,” which would be the spring of 1967 or thereabouts. Lawrence Dietz’s 1968 New York article says the dismantling happened at around the time Van Dyke Parks’ album Song Cycle was released. That was in November 1967. Perhaps we should say that it likely happened sometime in 1967, and leave it at that.

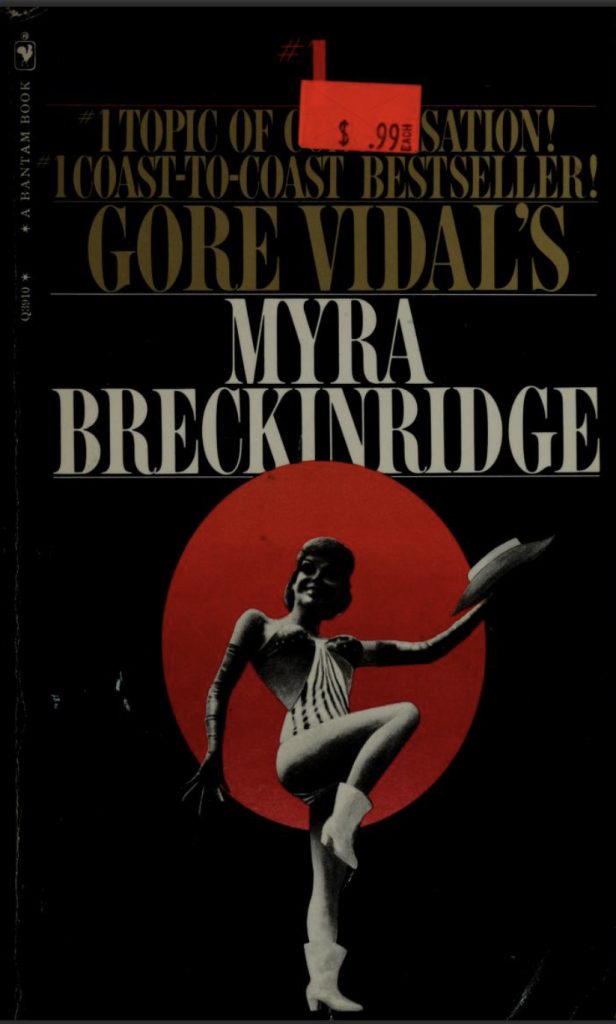

In any event, shortly after the Sahara Lady vanished, she made a strange comeback thanks to Gore Vidal’s famously scandalous 1968 Hollywood novel Myra Breckinridge. The book featured the statue on the cover and, inside, as a recurring totem (“[S]he is, to me, Hollywood. She must never not be allowed to dominate the Strip”). Vidal had become acquainted with her in the 1950s when he was living in the Marmont and working on screenplays for MGM.

In any event, shortly after the Sahara Lady vanished, she made a strange comeback thanks to Gore Vidal’s famously scandalous 1968 Hollywood novel Myra Breckinridge. The book featured the statue on the cover and, inside, as a recurring totem (“[S]he is, to me, Hollywood. She must never not be allowed to dominate the Strip”). Vidal had become acquainted with her in the 1950s when he was living in the Marmont and working on screenplays for MGM.

Vidal’s book was a sensation, and 20th Century Fox soon began work on a film adaptation. To promote the book and whet audiences’ appetite for the upcoming movie, the Sahara Lady went on tour. According to copious newspaper coverage at the time, a famously gonzo press agent named Jim Moran found the figure at a dump in the San Fernando Valley and purchased her for $1,500. Moran wasn’t just a kindred spirit of Jay Ward Productions PR man Howard Brandy; Keith Scott notes that Boris Badenov once played a press agent named Jim Moranski and that both Paul Frees and Bill Scott imitated the real Moran’s distinctive voice “whenever there was a small-time crook or a show-biz type” in a Ward cartoon.

Moran put the Sahara Lady on a trailer and sent her on a cross-country tour, offering her to officials in major cities and making helpful proposals such as San Francisco placing her on Alcatraz Island or Baltimore swapping her in for George Washington at Mount Vernon Place. (He got no takers, which was presumably the point.) He called the showgirl “Myra Breckinridge,” a retconning we’ll ignore here, since she was never known as that when she stood atop the Sahara sign.

When Myra Breckinridge the movie arrived in 1970, its makers included scenes restoring the Sahara Lady to the Marmont, though not with her sign and not in the same spot across the Strip from Bullwinkle. According to Shawn Levy’s The Castle on Sunset, the movie’s showgirl was a reduced-size replica of the original; if so, it’s a very faithful imitation. And given that press agent Moran had apparently procured the actual Sahara Lady to promote Myra the book and movie, it’s not clear why they would have needed to fabricate a substitute. (Levy says that along with reappearing outside the Chateau Marmont for filming, the figure made a second return as part of a billboard for the movie.)

When Myra Breckinridge the movie arrived in 1970, its makers included scenes restoring the Sahara Lady to the Marmont, though not with her sign and not in the same spot across the Strip from Bullwinkle. According to Shawn Levy’s The Castle on Sunset, the movie’s showgirl was a reduced-size replica of the original; if so, it’s a very faithful imitation. And given that press agent Moran had apparently procured the actual Sahara Lady to promote Myra the book and movie, it’s not clear why they would have needed to fabricate a substitute. (Levy says that along with reappearing outside the Chateau Marmont for filming, the figure made a second return as part of a billboard for the movie.)

Raquel Welch, who played Myra, appeared on the poster and in movie scenes as the Sahara Lady brought to life. The X-rated film turned out to be a bomb of legendary proportions, panned by everyone from Gore Vidal himself to Leonard Maltin. If the Sahara had any pangs of regret about taking its sign down before the Myra book and movie brought it so much publicity, they probably faded quickly.

And with that, the Sahara Lady’s brief return to fame fizzled out. Once celebrated, she isn’t quite entirely forgotten: In 2019 alone she turned up in both The Castle on Sunset and Guy Davidson’s Categorically Famous: Literary Celebrity and Sexual Liberation in 1960s America, the latter of which devotes a large chunk of its Myra Breckinridge chapter to the showgirl. But when she’s remembered, it’s usually for her association with something else: the Chateau Marmont, Myra Breckinridge, or Bullwinkle J. Moose.

What happened to the figure? I don’t know. I don’t know if any living person does. The New York Public Library is home to press agent Jim Moran’s collection of artifacts concerning his career, and the online catalog makes no mention of a 15-foot woman. Having acquired her from a dump, he may have returned her to one after her national tour ended.

If anyone knows of her current whereabouts, there may be money in it. The current proprietors of E.T. Legg & Associates, the company that has owned the land where the Sahara sign stood all along, have been looking for the Sahara Lady for years in hopes of reacquiring her. So far, their quest has been unsuccessful. But we can hope—or at least I do.

The Moose Stands Alone

“Promotional endeavors such as the larger than life statue of Bullwinkle and Rocky typify the flamboyant California lifestyle.”

—1980 American Airlines ad explaining California to Canadians

Without the Sahara Lady rotating across the street, the Bullwinkle statue was robbed of the context that inspired it. Yet it wasn’t merely a punchline that had lost its setup. The statue had secured its own share of fame as a symbol of the Sunset Strip, and when the producers of a 1969 French TV program about Los Angeles filled their show with imagery that might help viewers understand LA, Bullwinkle and Rocky got their close-up.

By then, the era of Jay Ward Productions engaging in extravagant publicity stunts such as Bullwinkle’s Block Party was long over. Still, Bullwinkle and Rocky retained their prominent spot on the Strip. A 1980 American Airlines ad aimed at Canadians even listed them among the reasons to visit California, along with movie stars and sun-drenched beaches.

You may have already noticed that the above ad depicts Bullwinkle in less-than-mint condition. Jay Ward had commissioned the statue to hype The Bullwinkle Show’s 1961 debut, and some of the materials involved—plaster, wood, cardboard, and newspapers—did not lend themselves to enduring good looks. Nor, after a certain point, did Ward take steps to keep the moose’s age from showing.

In November 1980, Leonard Maltin took this snapshot of the statue, with Bullwinkle—still in the paint scheme he’d gotten in the mid-1960s—looking downright shabby, and Rocky seemingly carrying a patina of grime. (I do like the shadow they cast.)

If you loved Bullwinkle and saw the statue in this period, you were probably deeply conflicted about the experience. Or at least a Boston-based fan named Michael Blowen was. He says that he considered the Bullwinkle statue “a great work of art and a great cultural symbol.” But on an LA visit in November 1984, he found the moose’s sad shape emblematic of “Hollywood letting its own history decay into decrepitude.”

The good news was that Blowen’s job—film critic for The Boston Globe—put him in a position to do something other than stew. He wrote a column, “Bring Back Bullwinkle’s Twinkle,” which decried the situation and quoted Bill Scott’s explanation for why the statue had been left to rot away: “Jay believes in Parkinson’s Second Law. That is—A Thing Reaches Perfection Just Before It Collapses.”

“It’s time stop this moose-guided man from ignoring our hero’s statue—before there’s nothing left of one of the only true Hollywood legends, Bullwinkle J. Moose,” wrote Blowen in his November 14, 1984 column. He also called on Bullwinkle fans to express their discontent during the question-and-answer session at the appearance Scott and June Foray would be making that evening at New England Life Hall.

I attended that joyous event, and am ashamed to say that I don’t remember if anyone spoke up on the statue’s behalf. But Blowen says that his column got a tremendous reaction. And the following March, when The Los Angeles Times reported that the statue had indeed been restored, it credited Blowen and an LA disc jockey, Dick Whittington, for prodding Ward to take action. “Jay finally bowed to intense, nationwide pressure,” explained Scott. Jay Ward Productions artist Sam Clayberger and his son fixed up the moose and squirrel, giving Bullwinkle’s suit a new paint job with blue, purple, and white vertical stripes in the process.

As Andrew Leal pointed out to me, the newly spruced-up statue is visible in an episode of the CBS show Crazy Like a Fox that aired on March 17, a couple of weeks before the Times took note of the restoration.

Blowen got thank-you notes from Scott and Foray and considers his role in rescuing Bullwinkle “my greatest achievement.” But it turned out that saving the statue wasn’t a one-time affair: Once refurbished, it began to decay again. It often looked like a piñata that had been left out in the rain.

By the time I first saw the Bullwinkle statue in person in 1988, Jay Ward Productions had been out of the animation production business for four years; Jay Ward himself would pass away in 1989. This photo I took shows the statue after the Ward studio had shuttered and been replaced by a tarot shop, with the Clayberger paint intact but an alarming crevice in Bullwinkle’s hip:

Some years later, the tarot shop gave way to a pet groomer called Hollywood Hounds, which—judging from the hostile vibes I got on one visit—regarded Bullwinkle as an unwanted totem. Here’s the statue after another repainting, with a rupture on the moose’s chest:

In the 21st century, Bullwinkle underwent yet another makeover—one that deprived him of the bathing suit that had originally alluded to the Sahara Lady’s skimpy togs. Instead, he got a look inspired by the Bullwinkle merchandising visuals of the time, with yellow antlers and a brown Wossamotta U turtleneck. But this version also soon sustained damage, with the moose’s right glove literally falling apart.

By 2013, Hollywood Hounds had closed, and PoshPetCare had taken its place. The Sahara Lady and Jay Ward Productions were long gone; even Dudley Do-Right’s Emporium was now a memory. With the era that gave us Bullwinkle’s Block Party having receding into the distant past, and the statue itself so fragile, it was a miracle it was still standing at all.

When We Last Left Our Heroes

”On July 22, 2013, Jay Ward must have been rolling in his grave. The statue had vanished! … There was no explanation or reason announced about its removal. Were Boris and Natasha operating the crane?”

—Alison Martino’s Vintage Los Angeles, November 18, 2013

The news broke via the Instagram feed of an actor named Tristan James Butler. On the morning of July 22, 2013, Bullwinkle and Rocky were plucked from their perch in front of PoshPetCare by a crane, then hauled away. And at first, as Alison Martino soon reported on her Vintage Los Angeles site, nobody knew where they were going, or why.

Martino, a cheerleader for Los Angeles’s quirky midcentury cultural history in general and the Bullwinkle statue in particular—“Sunset Strip’s Statue of Liberty,” she calls it—feared the worst. “Growing up in the seventies, and living not too far from Sunset Strip, I used to love seeing that as a kid,” she says. “I just thought it was very dreamy. It felt like a real-life cartoon. So when it disappeared, it was shocking.”

It wasn’t hard to deduce that the statue’s crumbling condition had something to do with its removal. PoshPetCare’s Facebook page gave the first hint of where it was headed: “Say bye to Rocky and Bullwinkle. They’ll be restored and moved to dreamworks!”

DreamWorks’ interest in the statue’s fate stemmed from the fact that it had bought Classic Media, which controlled the rights to Bullwinkle in partnership with Jay Ward’s family. Tiffany Ward, Jay’s daughter, still owned the statue and brokered the arrangements that led to it finally being uprooted from 8218 Sunset almost 52 years after Bullwinkle’s Block Party.

Though DreamWorks was indeed involved in the plan to save Bullwinkle and Rocky, they were actually headed to a Warner Bros. facility for restoration by Ric Scozzari, an artist, craftsman, and longtime friend of the Ward family. He’d also been responsible for the statue’s previous makeover—the one that gave Bullwinkle a Wossamotta U. sweater. Like earlier refurbishments, that one hadn’t done anything to make the statue more fundamentally robust, which was why he was again faced with the challenge of preserving it.

In the Wossamotta U. restoration, “I slopped plaster on it, like they used to do at Coney Island back in the 1920s,” Scozzari says. “But the elements got to it—the weather, the smoke, the rain just made it difficult to be out there,” he says. For his new renovation, “I thought I’d make it a lot more durable.”

Rather than just patching up and repainting the statue, Scozzari deconstructed and rebuilt it. “When we cut him open, it was just a plumber’s strap holding it together, wedged with wood to make the strap tighter,” he says. “So there was no integrity in the cross member where the arms and the body intersected.” Rummaging around inside the statue, Scozzari discovered a startling Easter Egg: one half of a W.C. Fields salt-and-pepper shaker set, presumably alluding to sculptor Bill Oberlin’s second career as a Fields impersonator. (Scozzari had previously found the other half of the set inside a wall at Dudley Do-Right’s Emporium when doing work on that building for the Ward family.)

Scozzari gave Bullwinkle new steel innards and a fiberglass shell coated in automotive-grade paint, finally freeing him from the curse of inexorably falling apart every few years. Just as important, he returned the moose to the look he had in 1961, red-and-white bathing suit and all. Working from vintage photos, the artist copied the original paint as closely as possible, down to the number of stripes on the outfit. He took only two major artistic liberties: He moved Bullwinkle’s pupils downward so that he’d appear to be looking at spectators below him, and he gave the moose hairs sprouting from his scalp to match the ones he sported in drawn form. (On the original statue, the hairs had been painted on and nobody could see them from the street.)

In October 2014, the freshly renovated Bullwinkle and Rocky returned to public display at the Paley Center for Media in Beverly Hills, as part of an exhibit on Jay Ward Productions’ work. Later, they got a showing at West Hollywood City Hall.

But where would the statue find a permanent resting spot? Among the rumored possibilities were the Television Academy building or a site on Santa Monica Boulevard in Beverly Hills. The most intriguing scuttlebutt—at least to those of us who live in Northern California—even theorized that it might migrate upstate to Berkeley, a city with deep Jay Wardian ties. (Ward and partner Alex Anderson produced Crusader Rabbit, the first made-for-TV cartoon there and named Bullwinkle after local Ford dealer Clarence Bullwinkel; Ward continued to own a real estate company in Berkeley for the rest of his life.)

The ideal location, of course, would be somewhere on the street Bullwinkle and Rocky had called home all along. That option came into focus when Tiffany Ward offered to give the statue to the City of West Hollywood if it would orchestrate its return to Sunset Boulevard. In March 2015, the West Hollywood city council voted to accept the donation and allocated $20,385 from the city’s Public Art and Beautification Fund toward the expense of placing it on public property. A happy ending seemed in sight.

Except it wasn’t that simple. The original plan to place it in a city-owned parking lot at 8775 Sunset fell apart over concerns that it would be overwhelmed by a planned 64-foot behemoth of an interactive billboard called the Sunset Spectacular, which wasn’t actually finished until March 2021. There might have worse fates for a statue whose very reason for being was to serve as ironic commentary on a giant advertising sign, but it’s nice that the city was taking the project seriously.

A new location was chosen on a traffic island at the corner of Sunset and Holloway Drive, a mile from the Ward studio’s former premises. The city favored it for several reasons: The statue wouldn’t block billboards or traffic lights there, and there would be adequate room for admirers to visit and snap photos. Even then, there was some opposition from residents of the West Hollywood Heights neighborhood, who expressed concern about the possible influx of Rocky and Bullwinkle fans. But at a meeting on August 19, 2019, council members heard both sides and voted unanimously to go ahead, at an estimated cost of $108,467, including the construction of a new 6-foot base.

Bullwinkle and Rocky weren’t actually hoisted onto that base until February 2020, six and a half years after they’d been evicted from their original digs. An unveiling and rededication were scheduled for March 28, 2020, then canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic—robbing those of us who weren’t alive in 1961 of our chance to attend the closest thing this century was likely to get to its own Bullwinkle’s Block Party.

With Bullwinkle and Rocky sturdier than ever, owned by the City of West Hollywood, and ensconced on public property, there’s every reason to believe they’ll be with us for a long time to come—something that was never clear when they were lingering at the former Jay Ward Productions. Still, a traffic island is not an entirely idyllic place. As writer Mark Evanier said on his blog in March 2020, “I know that intersection and I’ll bet you a round-trip ticket to Moosylvania that within the next few years, some drunk driver’s going to plow into it, making for very funny headlines and Restoration #3.”

Someone may owe Evanier that ticket. On December 1, 2020, a three-car accident at Bullwinkle’s traffic island scuffed the statue’s base. And then, shortly after 2:00 a.m. on Saturday, July 24, 2021, a speeding orange BMW Gran Coupe being pursued by the police struck the statue before flipping over nearby, sending the two people inside to the hospital.

The latter incident left the BMW barely more than a heap of crumpled steel and shattered glass. Once again, the statue’s base was damaged. Bullwinkle himself suffered cracked ankles. But he stayed up, with the help of a support beam and some rope. What might have happened if he were still made of plaster and papier mâché, I don’t even want to contemplate.

I still haven’t seen Bullwinkle and Rocky in their new location. In fact, I haven’t seen Scozzari’s restoration in person at all yet, having managed somehow to miss its Paley Center and City Hall appearances. When I finally do get to the corner of Sunset and Holloway, I expect a tearful reunion, and then many more visits to come.

Elbow Prints on the Sands of Time

“Ward, who it is rumored laughed instead of cried when he was slapped at birth, began as a small party-giver. His first party merely roped off a block-long portion of Sunset Boulevard, while the genial host, dressed in white tie, tails and sneakers, greeted guests at the unveiling of a statue of Bullwinkle in a forecourt decorated with elbow-prints of newsmen.”

—“Bullwinkle’s Boss Top Party-Giver,” Joan Crosby, August 12, 1963

Okay. We are, at long last, ready to return to the subject of those elbow prints in the forecourt of Jay Ward Productions. One can quibble with the above account of Bullwinkle’s Block Party given by syndicated TV columnist Joan Crosby a couple of years after the event happened. She’s apparently conflating Ward’s Bullwinkle Show premiere, where he wore a tux and sneakers, with Bullwinkle’s Block Party, where he came dressed in a Cleveland Indians uniform. And all of the elbow prints of members of the media which remain in that forecourt to this day carry dates later than September 20, 1961, the night of the Block Party.

But the fact that Crosby referenced the elbow prints at all, and said that they belonged to “newsmen,” is worthy of note. Later references to the prints tend to be fleeting and to say that they those of Ward associates. That’s true only of a few of them, mostly belonging to members of The Bullwinkle Show’s voice cast and their spouses. The book California Babylon even bizarrely claims they were left by friends of Fess Parker when he owned the building.

When I visited the prints in 2018, after the Bullwinkle statue had been removed, I was puzzled by most of the names I saw. Who were Budd Austin, Eve Starr, Dick Mathison, Lou Larkin, and Bev Copeland? Could there be so many Jay Ward staffers I’d never heard of?

I began plugging the mystery names into Newspapers.com. Soon it was apparent that the elbows—most of them, anyhow—belonged to Los Angeles-based journalists who wrote about the TV business. Some of them were people who, judging from their work, were enthusiastic Bullwinkle fans.

The first reference I can find to the elbow prints is in a September 24, 1961 Boston Globe article about The Bullwinkle Show by Elizabeth Sullivan, who reported that she had been invited to leave her prints during her next visit to Hollywood. There’s no evidence that happened. But 18 other journalists did get to participate, along with a few Ward employees, Ward-employee spouses, a photographer, and a smattering of people who remain enigmas to me.

Most of the prints were left on four Tuesdays in November and December of 1961, during The Bullwinkle Show’s prime-time run. At least two of the TV writers honored—Hal Humphrey and Allen Rich—wrote about the experience at the time. Humphrey says that Ward asked him to attend a dinner party and the elbow ceremony by sending “a pretty brunette in a modified Gay 90s bathing suit” carrying “an engraved invitation a yard long” to his office.

Allen Rich, meanwhile, reported getting his invitation by phone:

The voice on the telephone was enticing. It said, “We would like you to bend your elbow. The Bullwinkle Show and its producer Mr. Jay Ward will be your host at Frascati’s [a popular Italian restaurant located a couple of blocks from the Ward studio].

After due consideration (three seconds) I said, why that is just fine. I will be glad to bend my elbow at Frascati’s and I only hope they have my favorite brand.

“No, no. You do not understand. The brand is only incidental to the main attraction,” said the voice.

“So what is the main attraction?” I asked.

“You. We want you to bend your elbow, put it in the cement in front of the large and imposing statue of Bullwinkle on Sunset Boulevard. Then we will write your name and the date in the wet cement and it will remain ever enshrined for posterity. This is an honor we are according to a few of the columnists, and it is a very great honor indeed.”

Humphrey says that a three-piece band played “There’s No Business Like Show Business” during the ceremony, as “Ward and Scott poured champagne from one of ‘Bullwinkle’s’ boots.” He adds that “a few curious passers-by stopped along the street momentarily, but seeing nothing unusual for this particular neighborhood, they didn’t tarry.”

Most of the elbow-print honorees are no longer with us—no surprise given that some were veteran scribes even 60 years ago. But I was delighted to find that one, Larry Tubelle, was active on Facebook and that we shared a friend, Seth Socolow. (It’s a small world.) Once Seth connected us, it turned out that Tubelle not only remembered the night when he left his prints, on December 5, 1961, but treasured it.

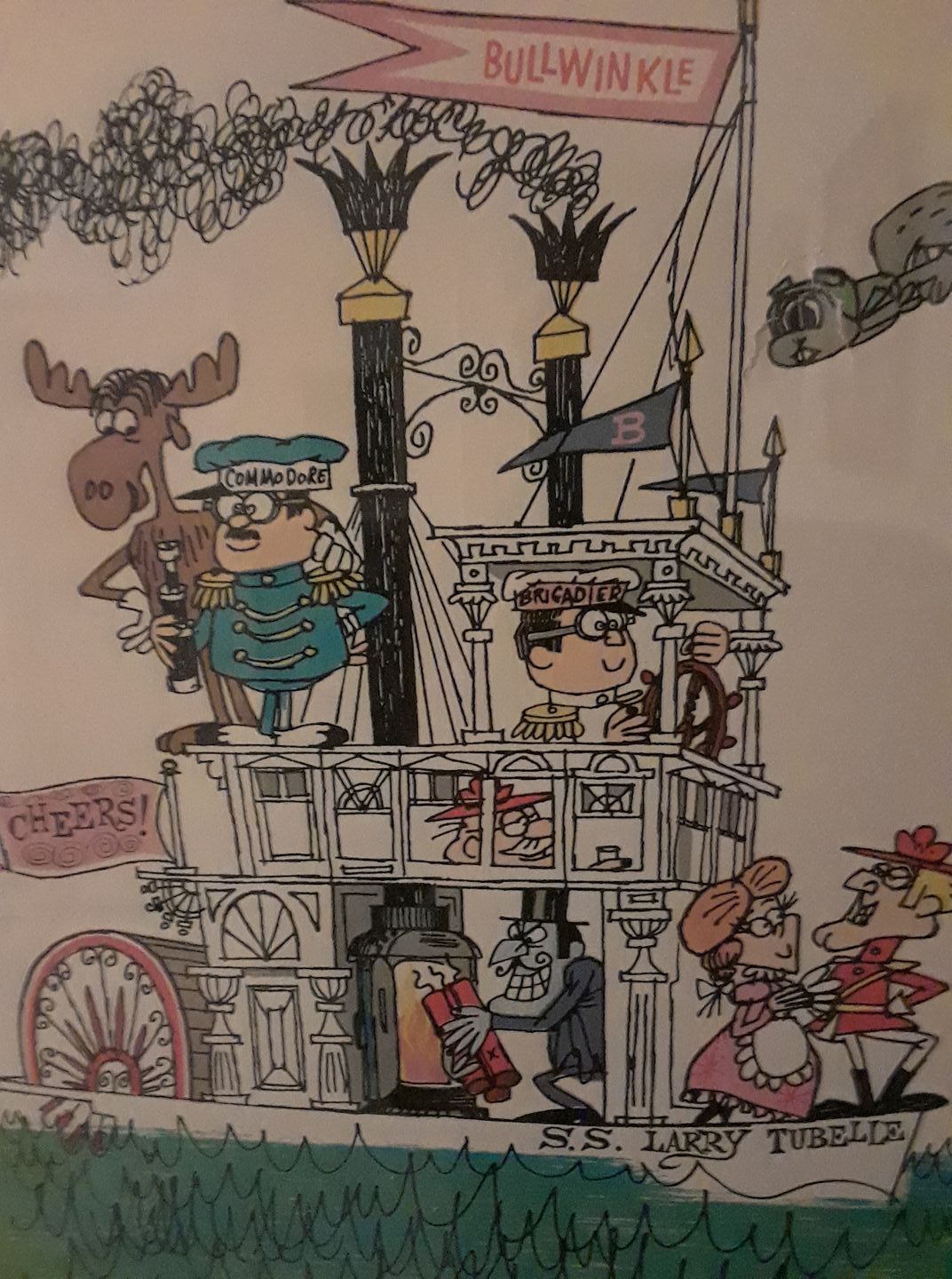

“My wife and I were invited to the party by Ward, probably because I’d given his Bullwinkle Show a favorable review in Daily Variety, where I worked as head critic in 1961,” he remembers. “It was one of the most enjoyable, rowdy, and plastered evenings of my long life. Jay was a great host.” The studio also presented Tubelle with a framed drawing of Bullwinkle, Dudley Do-Right, Inspector Fenwick and his daughter Nell, Snidely Whiplash, Jay Ward, and Bill Scott aboard a steamboat identified as the S.S. Larry Tubelle, with Rocky rocketing toward them. It’s hung on his wall ever since.

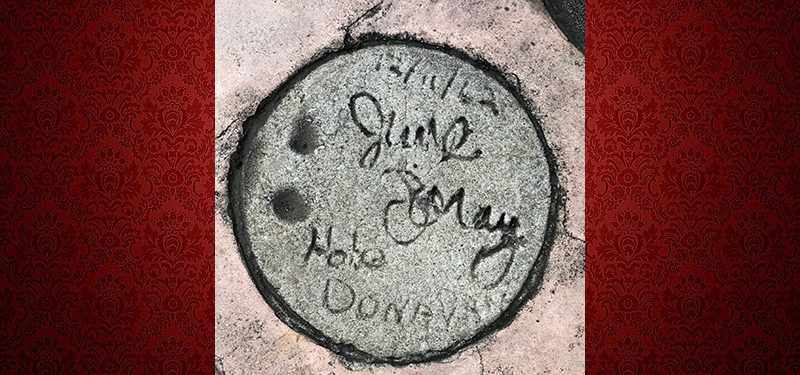

In its weekly sessions, Jay Ward Productions captured elbow prints of 22 people, most of whom were journalists, plus a few spouses. And then it stopped the mass inductions, as if it had honored every writer in Hollywood who was partial to Bullwinkle. But the following April, it revived the practice for a segment of Here’s Hollywood, a TV program hosted by big-band singer Helen O’Connell. Snippets of some episodes of the show survive on YouTube, but not either of the two in which O’Connell dropped in on the Ward studio. (Boy, do I ever hope they’re out there somewhere.) Her April 1962 visit inspired an unsigned, apparently syndicated article, “Quiet A.M. at Bullwinkle’s,” with a description of her elbow-print ceremony:

Attractive secretaries filled glasses as if they were used to it. As crew and production staff began downing the bubbly, a three-piece combo settled before a grand piano on the patio.

A huge cement statue of Bullwinkle pirouetted in front of the studios and Helen O’Connell, Here’s Hollywood‘s charming hostess, pointed to it and then to a circle of fresh cement in front of it.

The producers imprinted her pretty elbow in the fresh cement, making her a member of the Elbow Bending Society.

It was in honor of this event that the champagne was served. They always do at Jay Ward’s. Doesn’t everybody?

A 1991 public-TV documentary about Jay Ward Productions, Of Moose and Men, includes what seems to be a photograph of O’Connell showing off her cement-encrusted elbow immediately after leaving her print, flanked by Scott and Ward and with the left edge of the Sahara sign visible in the background.

That December, the studio held its final Bullwinkle Show recording session. Once it concluded, the voice cast–Bill Scott, June Foray, Paul Frees, and William Conrad–left their elbow prints in what was apparently the final group elbow-imprint party. Hans Conried—not part of the session, but then the host of Ward’s show Fractured Flickers—joined them. I wondered why Jay Ward himself didn’t leave an imprint until I realized that Bill Scott did so not as a writer/producer but as voice talent.

It’s difficult to imagine a more fitting way for Ward to have wrapped up the elbow print tradition. And indeed, the end of Bullwinkle Show recording sessions pretty much coincided with the end of Jay Ward Productions’ nutty PR gambits, which had peaked the previous October with the “Statehood for Moosylvania”campaign. (It involved Ward and PR guru Brandy driving across the country in an elaborately decorated van, hoping to meet with JFK at the White House—but arriving when he was otherwise occupied with the Cuban Missile Crisis.)

NBC cancelled The Bullwinkle Show in 1964. The live-action Fractured Flickers, which was aimed at silly adults, got its share of attention from the press. But Ward’s last two animated series, Hoppity Hooper and George of the Jungle, retreated to kid-oriented time slots. And then the studio focused mostly on commercials for Quaker Oats cereals such as Cap’n Crunch until it closed in 1984.

No prime-time Ward shows meant little press coverage, and little incentive to continue the elbow-print ritual. The 30 cement circles with prints and signatures would stay scattered among an even larger number of blank circles—an unchanging, mostly unseen tribute to a particular moment in time.

Since nobody else seemed interested in doing it, I decided to document the elbow honorees. I figured out who almost all of them were—a few remain largely mysterious—and they would be an interesting group of people even if they hadn’t left their elbow prints at the base of the Bullwinkle statue.

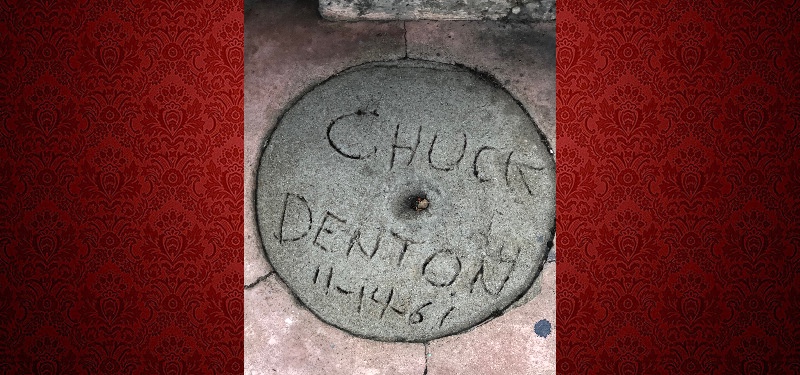

Inducted on November 14, 1961

Charles Denton was a syndicated TV columnist who wrote about Bullwinkle at least once. In 1963, he became TV critic for the San Francisco Chronicle and later went into public relations, representing a salt company. At the time of his death in 2002, he had lived outside San Francisco in Tiburon–also the home of Paul Frees–for more than 40 years.

Not the hockey player, but a Los Angeles Herald-Examiner TV writer, Bob Hull may have been the first person to call Elvis Presley “Elvis the Pelvis,” at least in print. I thought that the writing on the lower right-hand side might have been left by his wife, but Hull’s daughter Candace pointed out that it’s a “61,” separated from its “11/14/” on the other side.

Hal Humphrey, who got his start as a Mexico City-based reporter for TIME, was a TV writer and editor for the Los Angeles Mirror News, the LA Times’ afternoon tabloid. Later he wrote for the Times itself. As of 1958, his column was syndicated to 65 papers, making him the nation’s most widely-read TV columnist, at least according to the Mirror News. He wrote about Ward’s shows often and died in 1968 at the age of 58.

Hal Humphrey, who got his start as a Mexico City-based reporter for TIME, was a TV writer and editor for the Los Angeles Mirror News, the LA Times’ afternoon tabloid. Later he wrote for the Times itself. As of 1958, his column was syndicated to 65 papers, making him the nation’s most widely-read TV columnist, at least according to the Mirror News. He wrote about Ward’s shows often and died in 1968 at the age of 58.

Inducted on November 28, 1961

Charles “Budd” Austin was a syndicated Hollywood columnist who married the niece of songwriter/producer Arthur Freed. He was also a press agent for Debbie Reynolds, John Wayne, and Pat Boone, and later did PR for the Ice Capades and Georgia Power. He died in 2009.

Rowland Barber was a writer with lots of fascinating credits, including having written Rocky Graziano and Harpo Marx’s autobiographies as well as the book that inspired the film The Night They Raided Minsky’s and the screenplay for The 30 Foot Bride of Candy Rock, Lou Costello’s solo vehicle. He did write about TV, and was eventually west coast editor for TV Guide. But he was probably on the elbow-print invite list because he was a friend of Jay Ward Productions: His son David Nicoll Barber recalls visiting the studio with his dad and says that June Foray and Ward artist Bill Hurtz were frequent guests at the Barber home. Barber’s elbow prints looks for all the world like they’re dated 11/28/06, but presumably date to the November 28, 1961 ceremony.

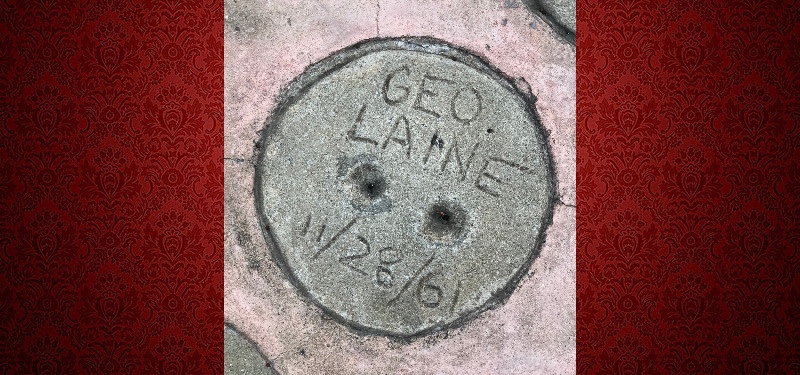

George Laine wrote about TV and other topics for Southern California papers, including the Long Beach Independent and Palm Springs’ Desert Sun.

Harriet Margulies wrote for Radio Daily-Television Daily. I’m not sure if she’s the same Harriet Margulies who much later had TV jobs such as answering the mail of Quantum Leap fans and appearing in an episode of NCIS as “Attractive Older Woman.” [Update, 12/7/2024: Bill Scott documentarian Amber Jones pointed out to me that the Quantum Leap/NCIS Harriet Margulies died on October 30, 2021, shortly after this article was published.)

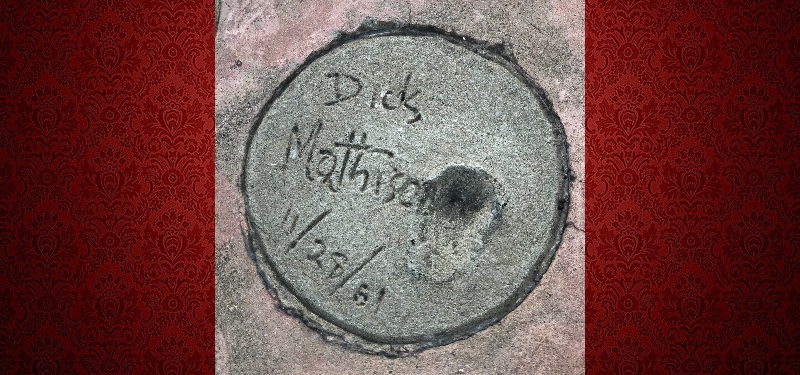

Richard Mathison spent time as the Los Angeles Times’ religion editor, but by the time he left his elbow prints at the Ward studio, he was west coast bureau chief for Newsweek. He ghosted autobiographies for Oscar Levant and Art Linkletter, wrote a biography of Howard Hughes shortly after the tycoon’s death, and had some accomplished kids: One was E.T. screenwriter Melissa Mathison, another was a judge, and a third wrote for TIME and People.

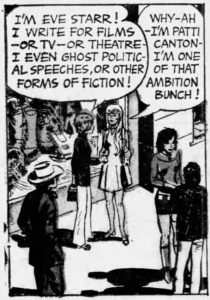

Eve Starr wrote about movies and TV and had a column called The Starr Report, where she wrote approvingly about The Bullwinkle Show and Jay Ward. (She did, however, refer to Bullwinkle as an elk, and I can’t decide whether it’s funnier if that were a sly joke or a misapprehension.) In 1969, Starr married Bill Kennedy, the aforementioned fellow columnist/Bullwinkle fan known as “Mr. L.A.” And in 1973, her friend Milton Caniff turned her into a writer character in Steve Canyon, who reappeared in 1977.

Inducted on December 5, 1961

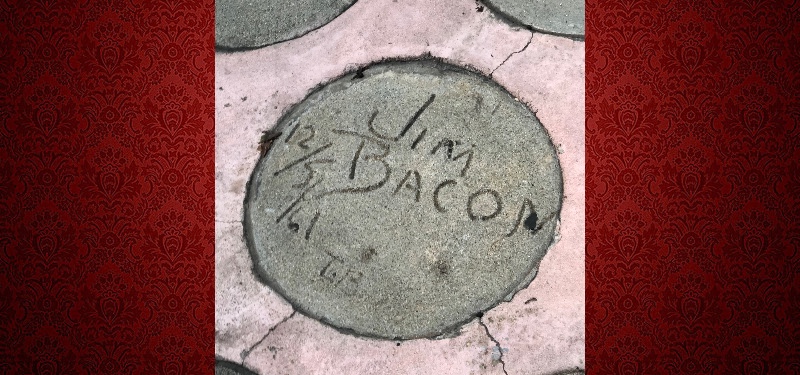

Jim Bacon was a legendary Hollywood columnist for the AP and Los Angeles Herald Examiner, famous for his tight relationships with Frank Sinatra, Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor, and others. Bacon was one of the reporters involved in the 1972 press conference that Howard Hughes dialed into to deny having written the memoir that Clifford Irving (it turned out) had fabricated. He also had a radio show and appeared in bit parts as an ape in four Planet of the Apes movies. He died in 2010 at the age of 96. The “TB” on his disc, I imagine, are the initials of his wife at the time, Thelma Love Bacon. Oh, and a bit he wrote about the premiere of The Bullwinkle Show includes a glorious fact I’ve never seen anywhere else: Jay Ward Productions was the only animation studio that gave out Green Stamps.

Jim Bacon was a legendary Hollywood columnist for the AP and Los Angeles Herald Examiner, famous for his tight relationships with Frank Sinatra, Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor, and others. Bacon was one of the reporters involved in the 1972 press conference that Howard Hughes dialed into to deny having written the memoir that Clifford Irving (it turned out) had fabricated. He also had a radio show and appeared in bit parts as an ape in four Planet of the Apes movies. He died in 2010 at the age of 96. The “TB” on his disc, I imagine, are the initials of his wife at the time, Thelma Love Bacon. Oh, and a bit he wrote about the premiere of The Bullwinkle Show includes a glorious fact I’ve never seen anywhere else: Jay Ward Productions was the only animation studio that gave out Green Stamps.

The west coast editor for TV Guide, Beverly Copeland left the magazine in 1964 to edit the program guide of Subscription TV, a very early pay-TV outfit run by broadcast pioneer Pat Weaver, Sigourney’s father. Later in the 1960s, she was the publisher of Better Health News.

John David Griffin was a TV columnist who got started at The New York Enquirer, a paper published by his father; he later had his own radio show, The World of John David Griffin; gossip columnists claimed he dated Connie Francis. Like several of Ward’s elbow-print honorees, he later went into PR. He was only 45 when he died in 1973.

A Susan Harbach pops up so often in the Los Angeles Times’ society pages of the era that–absent further information on her–I think we can say she was a socialite. She added flourishes to her elbow prints such as pie-like indentations along the perimeter and the inscription “For B,” and while we may never know for sure who “B” is, any Jay Ward fan would begin by guessing it might conceivably allude to Bullwinkle. Or Boris Badenov. Or Bill Scott?

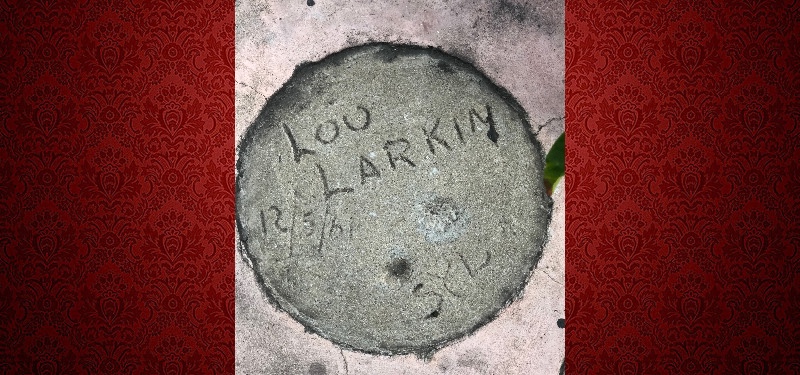

Lou Larkin wrote for both the Los Angeles Mirror and the Times, and though he did cover entertainment at one point, the Mirror later ran ads playing him up as a hard-hitting investigative reporter, covering topics such as a young boxer who fell victim to heroin and LA’s disc jockeys “as they really are.” He also wrote a feature on the Sunset Strip, well before the Sahara Lady and Bullwinkle settled there. I haven’t found anything he wrote about Jay Ward. His prints share a disc with one signed SYL; whether this is short for Sylvia or someone’s initials, I’m guessing it’s most likely his wife.

Dale Olson wrote for Box Office and Daily Variety, but became much better known after he went into public relations not too long after leaving his imprints. He worked for powerhouse PR firm Rogers & Cowan and formed his own consultancy, and–among many other gigs–advised Rock Hudson both before and after the actor acknowledged he had AIDS. He died in 2012.

Larry Tubelle is a former writer for Daily Variety, where he reviewed TV shows and became chief film critic. More recently, he has been active in tennis and has written plays. I’m happy to say that he shared his fond Jay Ward memories with me for this article.

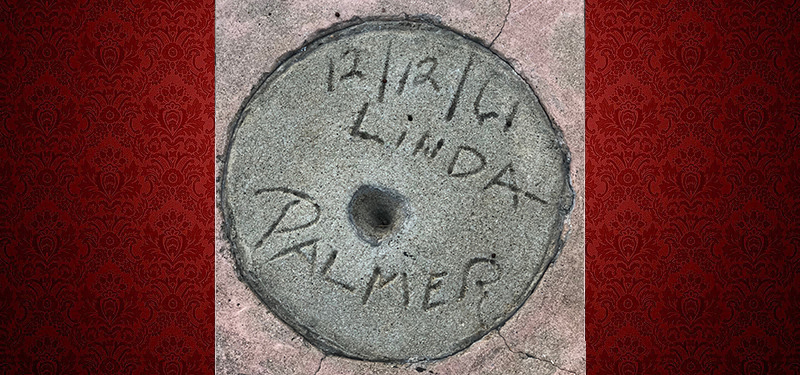

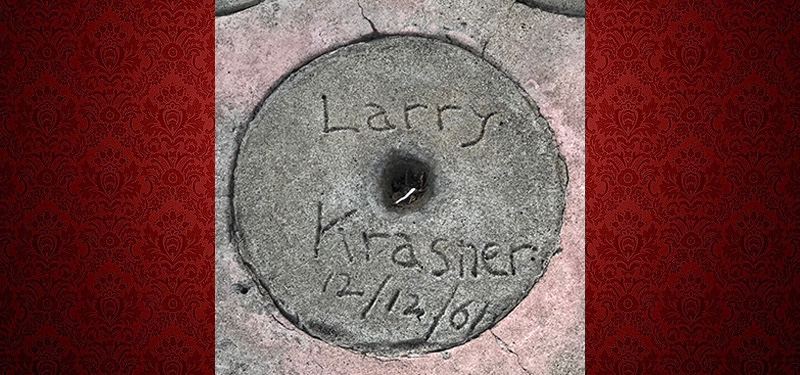

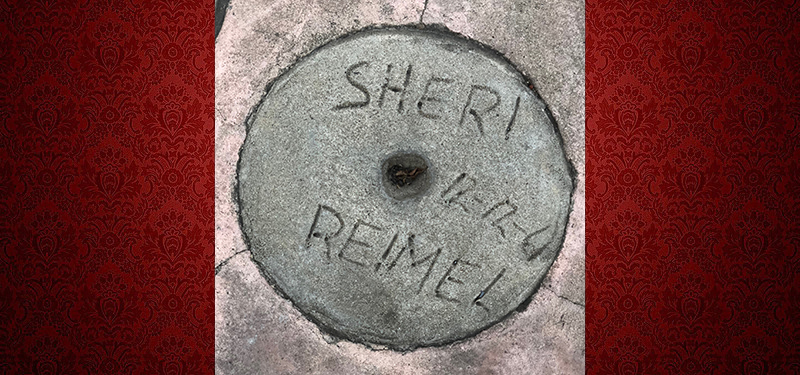

Inducted on December 12, 1961

Possibly the most high-profile entertainment writer here, Charles Champlin spent 17 years at LIFE and TIME, and I believe he was at one or the other when he left his elbow imprints. (As a former TIME writer myself, that pleases me.) He later became a very well known critic for the Los Angeles Times and a TV personality. More to the point, he called The Bullwinkle Show “the Krazy Kat of the televised cartoons.” He died in 2014.

In the early 1960s, Linda Palmer was an LA-area photographer. Thanks to elbow-print inductee Allen Rich’s account, we know that she shot pictures at the 12/12/61 party/ceremony when she left her own print. But that’s just the tip of her résumé: She later became a mystery novelist, screenwriter, VP of production at Tri-Star, and author of a still-available book on writing movies. She died in 2013.

Charles Witbeck was a TV writer, for King Features among other venues; when The Bullwinkle Show debuted, he wrote a long and appreciative article about it. His byline seems to fade away after the early 1990s.

Charles Witbeck was a TV writer, for King Features among other venues; when The Bullwinkle Show debuted, he wrote a long and appreciative article about it. His byline seems to fade away after the early 1990s.

I’ve found references to one or more guys named Larry Krasner involved in sales relating to radio and movies, but I’m not positive they’re all the same Larry, let alone the one who left his elbow print.

Allen Rich was yet another TV (and radio) critic, for the Hollywood Reporter and Hollywood Citizen-News among other publications, who also had TV and radio shows of his own. He retired in 1972 and died on New Year’s Day 1984; we can safely assume that Ruth was his wife.

I’ve found a couple of references to a Sheri Reimel who lived in Southern California in this timeframe, but nothing of substance or which would explain her elbow-print honor.

Inducted on April 3, 1962