First, an apology: It’s taken far too long for me to shower praise on The Noble Approach: Maurice Noble and the Zen of Animation Design, by my friend Tod Polson. It’s not just the best animation book of 2013; it’s among the most memorable ones on the subject, period.

Back when I hung out with Maurice — from the early 1990s until a few days before his death in 2001 — he frequently talked about the book which he was going to write. He did provide notes behind which Tod drew on, but they weren’t anywhere near enough to complete the book. So Tod drew on his own deep knowledge of Maurice’s approach, which he learned as one of the young “Noble Boys” who worked with Maurice at Chuck Jones Productions and elsewhere in the 1990s. He also interviewed others who Noble mentored, and quotes extensively from interviews with Maurice (including, I’m honored to say, the one I did). Essentially, he put together a jigsaw puzzle for which Maurice had only left a few pieces behind. And it works.

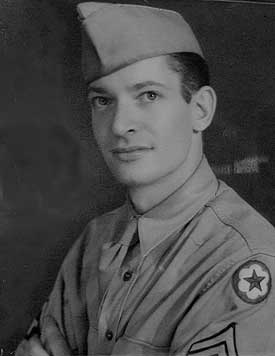

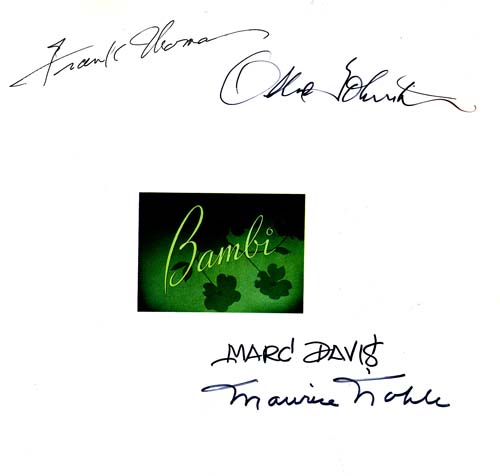

So this book isn’t exactly the same one which Maurice would have written if he’d completed it, but that’s O.K. It’s wonderful. And some of what’s good about it likely wouldn’t have been part of a 100-percent Noble version, such as the biographical section near the start, which takes us from his youth through his work at Disney, Warner, and elsewhere all the way to his final years as an éminence grise.

So this book isn’t exactly the same one which Maurice would have written if he’d completed it, but that’s O.K. It’s wonderful. And some of what’s good about it likely wouldn’t have been part of a 100-percent Noble version, such as the biographical section near the start, which takes us from his youth through his work at Disney, Warner, and elsewhere all the way to his final years as an éminence grise.

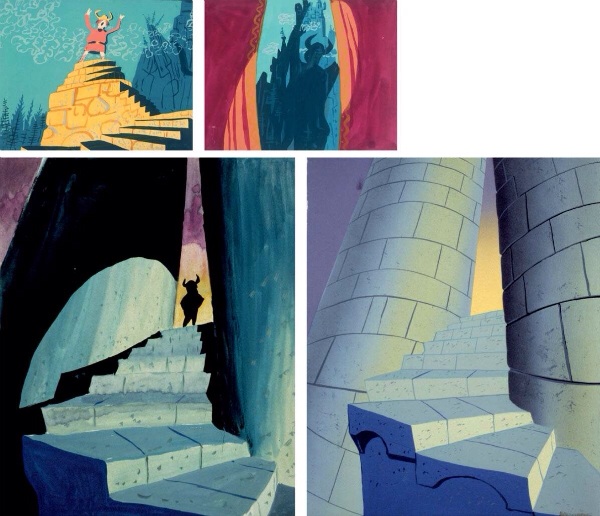

The book is presented as advice to those who wish to create animation, but it’s equally satisfying if all you’re looking is insight into what made Noble’s collaborations with Chuck Jones so special. For animation fans, it’s not necessarily even all that clear what a layout artist does; this book explains what Maurice did, and how it involved so much more than drawing backgrounds. His work helped set the mood; it influenced the humor and led to specific gags; it was a custom job each time, tailored to the needs of each film.

This is the best in-depth insider look ever published at how the Warner shorts were made from the perspective of someone who was there — it’s a far better read than Chuck Jones’ own Chuck Amuck and Chuck Reducks. And even though the book isn’t actually by Maurice, it does a perfect job of telling us what he did, and why.

Maurice had so many interests, and could talk entertainingly about so many subjects, that I spent surprisingly little time with him talking about animated cartoons. So for all the instances in which the book brought back pleasant memories, it also taught me things about his work which I didn’t know. For example, I wasn’t aware that he sometimes began by writing about what he hoped to accomplish with his layouts. The Noble Approach includes some of his longhand notes, as well as vintage photographs and a profusion of choice artwork from Warner and Disney as well as lesser-known stuff like his work on industrial films.

The Noble Approach is not the last book that anyone will ever need to write about Maurice Noble and his art. It’s a how-to which aims to put Maurice’s philosophies and techniques on paper, not an appraisal of his work. So it doesn’t explain why the best cartoons which Jones and Noble worked on together — mostly in the mid-1950s — or why, later on, even before the Warner studio closed, their partnership didn’t always result in magic.

It seems obvious to me that their work benefited from the tension present when both Jones and Noble were deeply and intellectually emotionally invested in a project; later on, when Jones handed over so much responsibility to Noble that Maurice sometimes got a co-director credit, Maurice’s designs no longer served to support the needs of a strong director, which is what he always said he was trying to do all along. When the most striking thing about a cartoon is the design, rather than the characters and storytelling — as is true of many later Jones/Noble films — something’s wrong. (The Dot and the Line is one exception, in part because it really was a tale told through design.)

Anyhow, objectivity was never the goal of this particular book. Tod has pulled off a spectacular feat. Reading this book made me smile in exactly the same way I did when I spent time with Maurice.

What’s Opera Doc? art at the top from The Noble Approach. Photo of Maurice Noble by me, taken in 2000 after we had lunch together in LA’s Chinatown; I think that’s Maurice’s leftovers in the bag he’s clutching.)

While I wasn’t looking, Bob McKinnon’s

While I wasn’t looking, Bob McKinnon’s