Please don’t try to use it right now–I’m intentionally crippling it at the moment. Thanks.

Can the MessageCenter Be Saved?

I’m going to try. I’m going to be experimenting with various tweaks to its settings which may help ward off spammers. If you do try to post, you may find some functions disabled–or you might not be able to post at all for awhile. I’ll see if there’s any way to outsmart the bad guys without dumping the board altogether.

If you see no spam on the board, that’s a good sign–you might try posting, if you have anything to say. Actually, I’d appreciate it.

Thanks in advance for your patience. The good news is that I’ve turned the tide against spam on the blog: Movable Type has identified and killed 182 spam feedback comments in just the past few days.

Half a Victory in the War Against Spam

As you may well have noticed, spam has rendered my MessageCenter completely unusable. Less obvious: There are also ongoing spam attacks against my blog. The spam-comments themselves usually show up in old postings, but when I weed them out, it’s tough to avoid killing good commenta, too. (I accidentally deleted one from Mark Mayerson this morning–sorry, Mark.)

The good news is that I just installed an update to my blogging software, Movable Type, which should do most of the work of purging spam from the blog for me. Keep your fingers crossed.

The bad news: I don’t know of any way to kill spam from the MessageCenter except manually, and it’s coming in far too fast to keep up with. And the software behind the message board hasn’t been updated in a very long time, so I don’t anticipate being able to solve the problem with technology. Unless the attacks mysteriously end soon, I’m going to have to find and install a new message board.

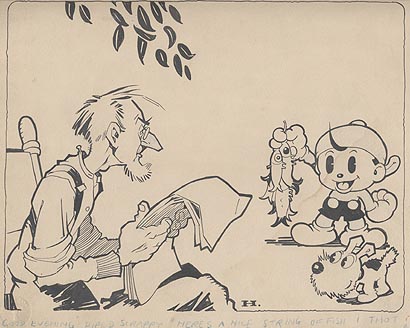

Huemerous Art

I’m tickled to report that the Scrappyland archives now contain their first piece of original art. It may well be one of the few extant examples of a Scrappy original anywhere, and it’s a doozy: a Dick Huemer drawing of Scrappy attempting to sell some fish to an elderly gent. Huemer was among other things a talented pen-and-ink man, and this piece shows off his distinctive linework to good advantage.

Looks like it may be from a book or story called “Scrappy Goes Fishing,” but I don’t know for sure. Do you?

Newgarden Noticed

Good piece on Mark Newgarden and his splendid collection We All Die Alone in today’s New York Times…

HarryGoRound.com is Live

For as long as I’ve had a Web site, it’s had a name (Harry-Go-Round) and a domain (harrymccracken.com) that haven’t been the same. I’ve finally gotten around to registering HarryGoRound.com, which now takes you to…Harry-Go-Round.

At some point, HarryMcCracken.com might evolve into a different sort of site. But it’ll always link through to Harry-Go-Round.

You have been warned. Or at least notified.

Happy Birthday, Al

Stephen Colbert’s The Colbert Report marked Al Jaffee’s 85th birthday today. I tried to find online video of the bit, which was funny (it may be on Comedy Central, but I can’t tell: Its videos won’t work on a Mac). Suffice it to day that Colbert waxed eloquent about the Mad Fold-In, then brought out a cake divided into three…and if you’ve ever read a Fold-In, you can pretty much fill in the gag from there.

(Am I the only one out there who had many, many memories of reading Jaffee’s stuff when I was a kid…but absolutely none of actually being amused by it? It was more transfixing than risible.)

Masters at the Hammer

Like Mike Barrier, I went to the massive Masters of American Comics exhibit in Los Angeles recently, but am only now getting around to reporting on it, on the day it closes. (It will show up in Milwaukee and New York later this year.)

Mike saw both halves, at the Hammer Museum and the Museum of Contemporary Art; I was in town briefly on business, on a day when MoCA wasn’t even open. So I only saw the Hammer half–focusing on newspaper strips and featuring work by Milton Caniff, Lionel Feininger, Chester Gould, George Herriman, Frank King, Winsor McCay, Charles Schulz, and E.C. Segar. Take my musings for what they are, then: a review of half of a museum exhibit.

Mike’s review reasonably takes issue with the selection of cartoonists that the show’s organizers chose. Any exhibit of master cartoonists that skips over Walt Kelly has a gaping void–I wonder if he was considered, and on what conceivable grounds he’d be excluded? But ultimately, I appreciated how the show provided lots of examples of the work of a few artists. (I counted about three dozen pieces by Chester Gould alone.) So I won’t quibble with their picks.

As you enter the gallery, a weighty introduction (“This exhibition has been founded on the premise that comics are a bonafide cultural and aesthetic practice with its own history, protagonists, and contribution to society…”) mentions the in-depth analysis that will follow. I was afraid that the comics would be accompanied by pompous, humorless commentary. I needn’t have worried–there were brief introductions to each artist’s work, but no thoughts or background on individual strips.

In some cases, strips badly needed explantion. There were two of Frank King’s Bobby Make-Believe strips–a sort of Little Nemo clone that also presaged the Gasoline Alley fantasy Sundays–but no mention of it whatsoever in the information on King’s work. I know enough about classic American comics that I knew what most of the stuff was; a patron with a less thorough knowledge of the artform’s history wouldn’t have known what some of the items were, or why they were there at all. (Even I was flummoxed in certain instances, such as by a non-comics drawing by Feininger which may have been in the show mainly because it had only one other Feininger original of any kind.)

As for the individual artists…well, any show with large quantities of McCay and Herriman originals would be worth a visit. I love Frank King’s work but hadn’t seen much in the way of his originals; spending some quality time with them was a delight.

Going in, I was a Segar fan who was dubious about whether looking at his originals would tell me anything that the old Fantagraphics originals wouldn’t. But seeing a bunch of Segar Sundays in large, crisp, black-and-white made me love him even more–they brought new clarity to his mastery of character, staging, and gag, and the examples were excellent.

At first, I also wasn’t sure whether Chester Gould deserved to be in the show at all, but I also got a lot out of the Dick Tracy section. As pure black-and-white compositions, Tracy strips in their prime were spectacular in a way I hadn’t understood. (Here again, though, I wish the organizers had provided captions to explain their choices–the show also had a 1970s Tracy strip that was weird and terrible, and I wish I knew why it was there.)

The last two cartoonists represented (in terms of organization, and maybe chronologically) were Milton Caniff and Charles Schulz, and both were disappointments. In the case of Caniff, there seemed to be a shortage of first-rate examples of his work. (I saw too many so-so later Terry strips with Hot-Shot Charlie, and not enough of the great 1930s era.) And there wasn’t much in the way of sequences of strips from Caniff, which was odd given that the organizers often resorted to proofs or newspaper tearsheets to show sequences of work, even for artists (such as Segar) who needed such treatment less than Caniff does.

With Schulz, the show really falls apart–there’s some good early and middle-period Peanuts, some less-interesting later examples, an example of his It’s Only a Game panel (sometimes ghosted, although I’m not sure about the one in the show; even when by Schulz, it’s a curiosity, not a masterwork), and several strips represented only in the form of cut-up tabloid-sized clippings. Schulz certainly merits inclusion in any show on masters of American cartooning, but his treatment here is so haphazard that it doesn’t make the case.

Do I sound like I didn’t have a good time? Naw–despite everything, I thoroughly enjoyed myself. The Hammer’s half of the exhibit wasn’t the definitive show on American newspaper cartooning, but as far as I know, such a show hasn’t been mounted yet. With all its faults, this one was a step in the right direction.

The handsome catalog is, in some ways, better than the exhibit itself. The strips look good, and the essays–but Stanley Crouch, Jules Feiffer, Pete Hamill, Patrick McDonnell, Brian Walker, and others–provide the analysis that the show itself doesn’t. If you like comics, you need it.

Jack Wild, 1952-2006

He shall be missed…

Another Visit to Pixar

On Saturday night, San Francisco’s Cartoon Art Museum held a benefit at Pixar in Emeryville. (This was the third such event; I wrote about an earlier one here.)

Once again, I was in attendance–and once again, I had a good time.

This one was a bit different than its predecessors. The last Pixar night was held shortly before The Incredibles premiered, and was in part a preview of that film. This time, we got to see a brief trailer for John Lasseter’s Cars, but that was it as far as stuff relating to the next Pixar feature went. (The art show from Incredibles which we saw last time was still up.)

I don’t think this was entirely because the studio doesn’t want to talk about Cars yet, since I’ve been to two public events (the less-than-spectacular Wondercon panel mentioned by Mike Barrier in a recent post, and an earlier session at an illustration conference, which dug into the film in some detail).

Unlike the earlier benefits, the bulk of last night’s presentation was done by one guy–Michael Johnson, a Pixar technical guy who’s also a board member at the museum. That was fine; he did a great job, giving a talk that was about both Pixar’s film-making process and its perspective on the world.

He began by stating three Pixar rules of success:

1. Casting, casting, casting. (ie, nothing is more important than the team you hire)

2. Hire people smarter than yourself.

3. Art as a team sport. (“51 percent is plays well with others.”)

One interesting thing about these three rules: They’re really one rule, since they could be summed up in one four-word one, namely Hire a smart team. Which sure seems to work for Pixar, and which is souund advice for any sort of creative or corporate endeavor.

Johnson showed some good clips as part of his talk, including several minutes of Andrew Stanton pitching Finding Nemo. (He was fabulous, and watching him in action made me wish that footage survived of Walt Disney in action during 1930s story conferences).

Brad Bird did about 3,000 drawings simply while reviewing work on The Incredibles (sketching with an electronic pen on top of CGI frames), said Johnson; he showed us a rapid-fire selection of those quick Bird drawings.

Other tidbits:

* Johnson said that all Pixar productions begin as 2D ideas. Some of the artists who work on ideas like to use real-world art materials; others work digitally, using Wacom’s Cintiq tablets. That’s fine: “We take no position on paper.”

* He showed a great little film about all the work that went into giving The Incredibles‘ Violet plausible long hair. It had never been done before and was a huge technical challenge: “Violet’s hair brought this production to its knees.”

* The DVD editions of Pixar movies are produced at the same time as theater ones, and are actually separate renderings composed for a TV’s aspect ratio. “We do it because we can.”

* Random quote: “We don’t want real-looking humans–they’re kind of creepy…reality is just a useful measure of complexity.”

* Another random quote: Effects animators “animate what the animators don’t want to animate.”

* Brad Bird and Andrew Stanton like to work with a traditional movie script; “John Lasseter, not so much.”

After Johnson’s talk, we saw One Man Band, the new Pixar short which will run with Cars. It’s fun and funny, with a storybook-like look that’s quite different from other Pixar work–and has, in a little girl character, one of the best actors ever to appear in CGI. Like all Pixar films, it also has sound that’s as rich, clever, and carefully thought-out as the visuals.

We then heard from co-director Mark Andrews and animator Angus McLane, and then we saw the short again.

One notable Pixar issue barely came up during the formal presentation: the little fact that it’s being acquired by Disney. But the evening ended with the Pixar staffers hobnobbing with attendees, and many of the questions focused on the merger.

Johnson said Pixar does want to make some sequels to its films, and that the studio, which is still a fairly small operation, will likely grow. He said he’s having fun talking to counterparts at Disney; Pixar is by necessity a secretive place, and he thinks it’ll be nice to have more colleagues to discuss things with. (But just how much sharing of technical know-how between Pixar and Disney will happen is yet to be determined, he said.)

(Side note on Pixar secrecy: Before we were ushered into the studio’s theater, we were wanded…and a guard examined my pen, presumably to make sure it wasn’t some sort of spy device.)

He said that Ed Catmull and John Lasseter have no plans to leave Northern California, but will likely spend a couple of days a week in LA. He also said that he fully expects to be at Pixar ten or twenty years from now: “As long as this place stays the same, this is where we want to be.”

If there’s another Cartoon Art Museum benefit, it’ll presumably be at a Pixar that’s an arm of Disney. I sure hope that there is another benefit, and that I get to go to it–and that the place still feels like Pixar. Much more important, I hope that the studio remains a place where people like Michael Johnson want to work for twenty years–and beyond. Time will tell…